Michael Thompson is a multimedia artist from Chicago, Illinois. One of his monoprints, “Nomenclature,” appears in Issue 41 of Blue Mesa Review, but perhaps his most provocative works are his fake postage stamps, which he has successfully mailed around the world. In late October, prior to the United States presidential election, I talked to him about his process, the way his work has been perceived globally, and the role of art and the artist outside of the “art world.”

Michael Thompson’s first collage (courtesy of artist)

How long have you been making art? How did you start? Were there any formative experiences looking at art that you recall?

I became an artist by mistake. I had a job in Pittsfield, Mass. working for VISTA (a domestic Peace Corps) and was helping convert a stationary store into a community arts center. I spent a few months on the job and upon completion the director of the center asked if I was interested in teaching a class at the center. Teach a class, I asked, in what? I was not an artist and had never taken an art class, but he said, teach a class in collage. What’s collage? I wondered. He explained what collage was and I went home that night and made a collage that to this day I still have and consider a wonderful piece and I was hooked on art. I taught collage at the center for 6 months and then decided to move to Chicago to attend the Art Institute of Chicago.

Your printmaking techniques are fascinating to me because you don’t often use the same methods I’m used to seeing often in museums, like screen printing or printing with linocuts. What draws you to monoprints and chine-colle and how do you find materials to incorporate into those pieces?

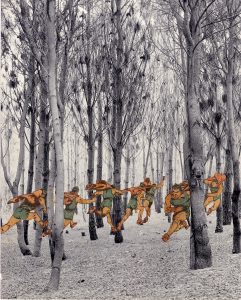

A piece made using both monoprint and collage techniques (courtesy of artist)

While at the Art Institute I fell in love with printmaking. I concentrated on monoprints, which allowed me to combine collage techniques with an element of fortuitous chance. The inking and removal of ink from the plate became selective and compositionally specific. It varied print to print and often resulted in happy coincidences. I was compelled to pursue mono-prints because I had very little money and couldn’t afford the new copper plates used in the department, so I recycled the backs of used plates, which forced me to concoct a new way to facilitate printmaking. I came up with a collage technique, essentially chine-colle (the bonding of lighter papers to a heavier support paper through the printing process) which offered the idea of “building a print” (upside down and backward) with the joy of seeing the completed piece after pulling the print off the press, finished! Eventually it occurred to me that I could use my tuition money to just buy my own press, which I did and have been using it ever since.

Could you tell us a bit about the piece that appears in Issue 41, “Nomenclature”?

Definition: “the names comprising a set”.

To me “Nomenclature” represents an image of false hope, or the faith in a set of beliefs that could ultimately prove spurious and fatal. Is “patriotism the scoundrel’s last refuge”? (Samuel Johnson) And what does it mean to suspend disbelief?

Do you find that you start with a conceptual idea and work from there? Or do you have an idea of the methods you’d like to use and then discover what ideas emerge from the final product? More broadly, how do you approach creating a piece of artwork?

I work in a variety of medium and the inceptions vary. For instance I make fake postage stamps, which masquerade as “real” stamps, are placed on addressed envelopes and dropped into mailboxes in the hopes of them being cancelled and delivered…and these require a full conceptual framework for them to be successful from the vintage envelopes, labels and stickers to the correct denomination and lay-out of the stamp.

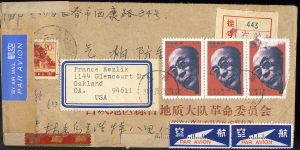

A stamp commemorating Tiananmen Square student-led demonstrations in 1989 (courtesy of artist)

Ultimately I have made stamps that have been mailed successfully from dozens of countries and I try to make them fulfill certain philosophical, political or humorous criteria. It’s easy to make a Chinese stamp depicting the Great Wall, but to make a stamp commemorating Tiananmen Square and have it cancelled in Beijing is so much more compelling.

Much of my work seems to begin with a vague idea about color or a pile of paper with images, text, forms or abstract shapes, and more often than not the original idea gets me working only to be modified as the work progresses.

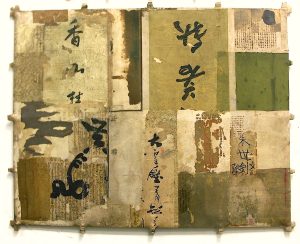

A kite (courtesy of artist)

The kites may be commissioned for a certain room with particular colors or can be simply based on a vague sense of calm, serenity or some other generality. They are really like paintings though and I often start by sketching lines and shapes, adding color, swatches of cloth or staining and slowly a cohesive whole begins to emerge.

My work with erector sets is generally based on the idea of a mechanical effect that I want to achieve and the process is to manipulate the toy girders and gears to achieve that result.

How have non-Western cultures influenced your work?

I make kites but they aren’t made to fly. While a student at art school, a kite flying competition was announced with the 1st prize of a case of beer. My friend and I were determined to get this beer, so we build a 6’ round kite with bamboo and canvas but the day of the competition was calm and windless and our kite couldn’t get off the ground. But my girlfriend convinced the Goodman Theatre to agree to have me hang multiple kites from the ceiling in the lobby and a career was born. I actually stumbled upon the East Asian influence when I was at an art stamp conference in South Korea and discovered the books and scrolls and fabrics available in antique stores. It was an amazing realization. I have returned to the Far East on numerous occasions subsequently with such rewarding results.

A memory jug (courtesy of artist)

Certainly experimenting with various mediums and forms appeals to me. I have spent the Covid-19 months creating Memory Jugs, historically the building up, mosaic-style, of small objects, trinkets, keepsakes and various items of sentimental value on a stoneware jug. I’ve been to London to search the Thames River foreshore at low tide where accumulations of broken pottery shards over the centuries have resulted in an activity called “Mudlarking”. The Thames foreshore considered one of the richest archeological sites in Britain. Building these jugs is 3-D collage.

There has been some controversy involving your work. Do you see your work as political? What purpose does art have outside of the “art world”?

Yes, there has been controversy involving some of my work, particularly the stamps, but not confined to them. For instance I once made a floating W.W. ll era mine, of Styrofoam and coffee cups (for detonators), painted it black and placed in the Chicago River. The next day, the Coast Guard and Police arrived to deal with what appeared to be a serious explosive ordnance disposal issue. It was soon discovered that the object was a styrofoam mock-up which they proceeded to destroy with their batons.

A floating WWII era mine replica, made of styrofoam and coffee cups (courtesy of artist)

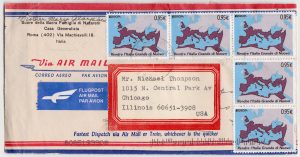

Dalai Lama stamp on a mailed envelope (courtesy of artist)

The stamps though have caused me the biggest problems. After discovering the riches of the Far East for providing kite-making materials, I began to travel to China on a regular basis. And each trip required a new Chinese stamp to mail; the tanks being stopped at Tiananmen Square, the Dalai Lama, Falun Gong, Xi as Winnie the Pooh, all controversial ideas in China. Usually half of these envelopes would be confiscated in China. I never mailed them to myself but used friends and relatives as recipients of the letters, so the Chinese wouldn’t know that I was responsible for the mailings.

Seven Years ago I was invited to participate in a show in Shanghai at the Dulan Museum. I decided to go to China for three months and create all my pieces there, so I had an apartment to complete the work in. I was picked up at the airport by staff from the museum. A week after arriving the local police came to my apartment to check my residency papers, which I had neglected to pursue for fear that vetting that application would unearth my association with the fake stamps. So, I began to submit my personal information to the Police to qualify for residency and during that process it was discovered, by State Security, that I was the guy who had been mailing these stamps for the past decade. Under the guise of meeting the Director, I was lured to the Museum and greeted by a dozen State Security Agents, who asked me if I was responsible for the fake stamps, and, as I had an envelope with the stamp I was mailing on this particular trip in my briefcase. I could hardly deny it. I was informed of the trouble I was in and after signing a statement attesting to that fact was ultimately offered the choice of jail or deportation (as I was a guest of the State I was given an alternative) After a long pause, I chose deportation, was taken back to my apartment, packed my bags, driven to the airport and made to buy a ticket out of the country. I picked Seoul because it was the cheapest flight available. I have applied in the years since for a visa but it is always denied.

“Make Italy Great Again” stamp, highlighting the Roman Empire (courtesy of artist)

The stamps have become very political. At their foundation, stamps are nationally issued and often represent a nation’s tradition and values which make them the perfect vehicle to satirize those traditions and values. A recent example that seems to fulfill a few of the requirements of a stamp was an Italian “Make Italy Great Again” stamp that highlighted the Roman Empire.

On the topic of the fake postage stamps, there has been a lot of controversy involving the USPS recently because of the upcoming election, in which more Americans than ever before are expected to mail in their ballots. How do you see your work with counterfeit postage stamps in the context of the pandemic and the new developments concerning postal service?

I am ambivalent about using the stamps during the 2020 Presidential election. The Postal Service is being crippled by budgetary restraints and a Trump appointed Postmaster General (Louis DeJoy) who has initiated a corporate reorganization, changed how letter carriers sort and deliver mail, eliminated late deliveries, reduced some hours of operation and removed sorting equipment in 600 regional post offices, all of which have “negatively impacted the quality and timeliness of mail delivery nationally”.

But I include the proper postage inside of each envelope I mail with my postage stamps with an explanation that this envelope is part of an art project. I sign and date that letter and self-cancel the stamp. In the event of another court case I want to be able to open any envelope with a flourish to prove my object is not to deprive the postal service of their proper revenue.

What are you working on now and what can we expect to see from you in the near future?

I’ve taken to canning vegetables in a pressure cooker, tomatoes are easy in a boiling water bath, but pumpkin requires a higher temperature. Having the pulp leads to pumpkin pies , working on my crust and ultimately entails eating a lot of desserts.

I enjoy working on the memory jugs. They are small, take a lot of time and require searching for and collecting materials. They are 3-D collage in the round.

I work on stamps intermittently these days. It relies a lot on friends going on trips and I would give them a few envelopes to mail, but travel is such a rare commodity these days. The process is more involved now, with packets sent to folks in foreign lands and them dropping the letters into the mail one at a time.

OM installation (courtesy of artist)

I recently installed a light-sculpture in a gallery window. It’s a small neon McDonald’s M and a blinking O, spelling “OM”. Taking a breath, relaxing. I wanted to spell M O F O but I’m still looking for the rest of the letters.

You can see more of Michael Thompson’s work at michaelthompsonart.com.

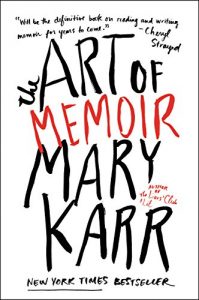

All this changed for me last fall, when I read The Art of Memoir by Mary Karr. Something inside me has always resisted the idea of books about writing books, but this one changed my mind. I read the whole thing—cover to cover—pen in hand, underlining a quarter of the text, and about 75% of the chapter, Dealing with Beloveds (On and Off the Page). Karr shares her process for managing her loved ones’ feelings about being included in her work in generous and thoughtful steps, 11 of them to be exact! Two of my favorites include a Herbert Selby quote, “If you’re writing about someone you hate, do it with great love,” and never claim authority over how people truly felt. Karr also recommends sharing parts of your work with the subjects on the page, especially if you think it “might make them wince.”

All this changed for me last fall, when I read The Art of Memoir by Mary Karr. Something inside me has always resisted the idea of books about writing books, but this one changed my mind. I read the whole thing—cover to cover—pen in hand, underlining a quarter of the text, and about 75% of the chapter, Dealing with Beloveds (On and Off the Page). Karr shares her process for managing her loved ones’ feelings about being included in her work in generous and thoughtful steps, 11 of them to be exact! Two of my favorites include a Herbert Selby quote, “If you’re writing about someone you hate, do it with great love,” and never claim authority over how people truly felt. Karr also recommends sharing parts of your work with the subjects on the page, especially if you think it “might make them wince.”