Staff Writes

Dispatches from the Blue Mesa Review Crew

Introducing: Co-Editors-in-Chief Amy Dotson and Gwyneth Henke

by Amy Dotson and Gwyneth Henke

Disgraced Fanfiction Writer to Bestselling Author: The Story of Cassandra Clare

Electra McNeil, BMR staff writer, tells the story of author Cassandra Clare.

When Words Starve You: A book review of Melissa Broder’s Milkfed

Mia Casas, writer and BMR reader, reviews Melissa Broder’s novel, Milkfed for Staff Writes.

Memory, Movement, and Tumbleweeds

Paris Baldante, graduate reader and staff writer for BMR, wonders about wandering.

Hidden Gems: My Favorite Writing Locations in Albuquerque

BMR’s undergraduate reader, Emilia Madrid, explores the options for local writers who are in need of a new location in Albuquerque to help overcome writer’s block.

Fragmented Ars Poetica for the Uncertain Present

Graduate reader and poet, Lucas Garcia, writes in response to the death of Palestinian poet Refaat Alareer.

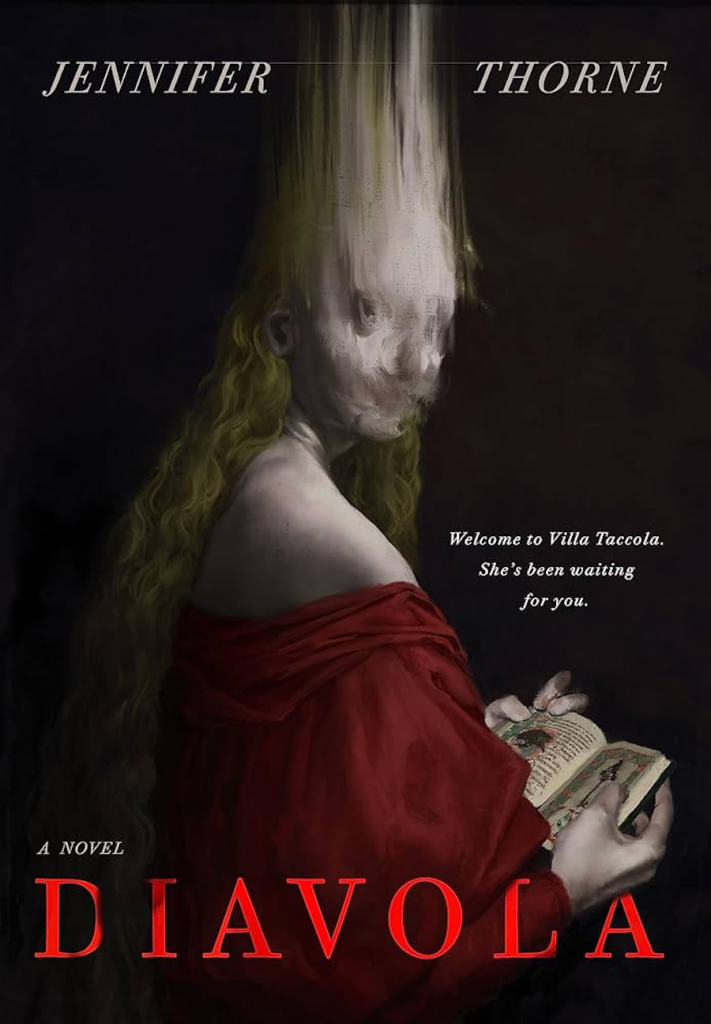

A Series of Unfortunate Events: Gothic Hits

Undergraduate reader, Alexandra Dark, writes for Blue Mesa Review.

Four Books Telling a New Story of the American West

Graduate reader and fiction writer, Julianne Peterman, writes about the American West through the lens of four books.

We Write to Heal Our Wounds: A Conversation with Michelle Otero

Shona Casey interviews Michelle Otero about her memoir, Vessels: A Memoir of Borders, for Blue Mesa Review.

Eat a Peach: a refreshing take on the celebrity memoir

Jordyn Bachmann, undergraduate reader, writes her review of David Chang’s book for Blue Mesa Review.

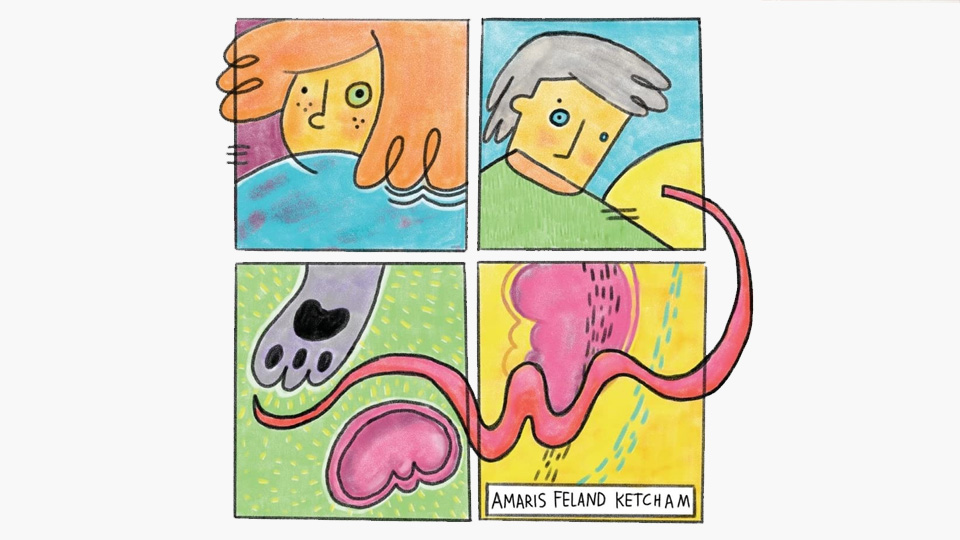

Unfiltered: An Interview with Amaris Feland Ketcham by Andrew Sowers

Blue Mesa Review undergraduate reader Andrew Sowers speaks with poet and graphic memoirist Amaris Feland Ketcham about her new graphic diary, Unfiltered: A Cancer Year Diary.

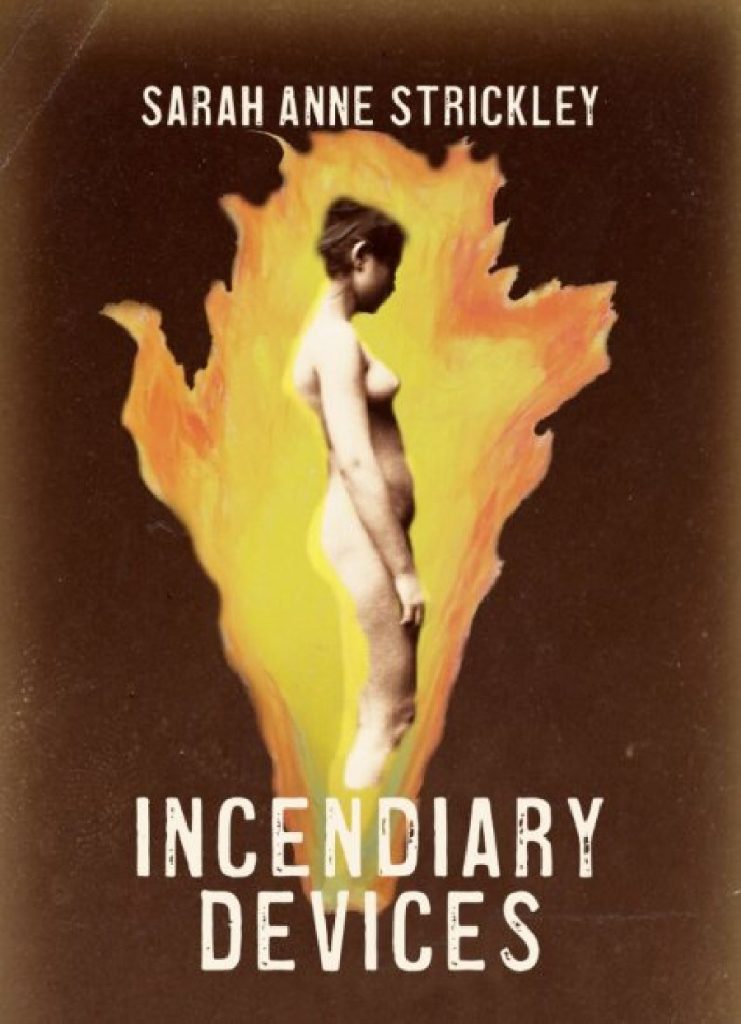

The Immense Sadness of the Unknown: A Review of Sarah Anne Strickley’s Incendiary Devices

MFA student Amy Dotson writes her review for BMR.

Art is Subjective

Kani Aniegboka, our creative nonfiction editor, writes about his expectations of art and narratives he’d like to read.

Be Contrarian, Be Passionate, Have Fun

BMR’s new fiction editor, Joe Byrne, on the kinds of work he wants to publish.