Letter from the Editor

Anthony Yarbrough

Tonight, the eve of a four-day break in rehearsals, they were to drive south to Mexico, arriving on Thanksgiving Day. She’d have the procedure and they’d head back as soon as possible. Stefan worked on Saturday; Gemma’s rehearsals resumed Monday and she had to be whole by then. No bleeding. No weakness. Please.

Not until Stefan reached for her pack did Gemma notice the couple in the back seat. “What the hell?” The woman’s pale face pressed against the window.

Stefan pulled her behind the lifted trunk lid.

“Who are those people?” She clutched her bag, heart a block of wood.

“They are going with us. She needs.” He lifted a shoulder against the word. “She’s in the same position you are.”

Her heart splintered, she gasped, “We,” and threw the bag at him. “We’re in this together.” She pushed his chest so hard he staggered.

Stefan closed his eyes against the sinking sun. “I should have said we.” He picked up her kit and put it in the trunk.

Earlier in the month, when her frantic search for an escape failed – the laws so bewildering, so certain of their rightness – she’d revealed her secret and her decision to Stefan. His ambition to sing was like hers to dance, so she believed he’d understand her need, but his reaction shocked her: rage, pacing, crying, begging her to change her mind, saying he’d take responsibility, marry her. He loved her. She pleaded in return: she loved him too but couldn’t have a baby before she danced the solo, before she had the career on which she’d based her whole life. He countered: some women want children their whole life. She backed away, arms crossed. She’d never been a girl begging to hold a baby or picking out names for future children. I’ll do this myself if I have to. I’m only me when I dance.

Faced with her fierceness, her need, he’d acquiesced and found the clinic, a miracle after her own fraught quest. She was nineteen but her failure diminished her back into helpless childhood. Please don’t let him hold it against me.

Now light drenched everything – old snow, leafless branches, the front of the apartment building – but as Gemma raised her face to the warmth, a cloud slid across. Teeth chattering, she said, “I can’t go. Not with people I don’t know.” Mittened hands in her pockets, she hunched against the cold. “Take them home.”

“Christ, Gemma.” Stefan flung out his arms and turned sharply away. “I can’t.” With a deep breath, he faced her. “Because…” His face opened. “Would you rather have the baby?”

“Don’t even ask.” She shivered violently. “It’s not a baby. Not yet.” She was whispering so the couple wouldn’t hear. “Send them away.”

“Gemma, please.” Stefan rubbed his hair. “They’re going to pay half the gas. 1200 miles. I can barely afford…” Again the word stopped him. “The procedure.”

“Abortion. Say it. And we will – oh shit.” She hadn’t thought about the cost, the distance. “Stefan, I barely make rent.” She’d failed as a we. His face was flat, uninflected; she couldn’t tell what he was thinking. Maybe her determination had forced his acquiescence.

“It’s all right.” His breath puffed white in the cold. “But I’m spending everything I saved to go to New York.” He touched her shoulder. “With you. I wanted to go with you like we planned.”

The sun dipped onto the mountains’ edge and the swirl of clouds over the city burst into gold. Her cheeks warmed. Her heart. Tentatively, she leaned against him and he put his arms around her, taking her weight. His strength loosened her words. “We will go, I promise. You’ll sing; I’ll dance. We can make another baby. Just later, when I’m too old to dance.”

“Promise?” When she nodded, he kissed her neck, held her tight for a moment, then took her hand. “Come meet Nancy and Greg.”

#

Six hundred miles south through Colorado, New Mexico, and a bit of Texas into Ciudad Juarez. As they began the long drive, the Rocky Mountains reared like cardboard cutouts against the sunset, then waned into nothingness. Little cities pooled in their own light – Colorado Springs, Pueblo – followed by little towns – Walsenburg, Trinidad – their light a mere spatter of stars along the freeway. Often the car slipped through total darkness as if along a ridge, both sides of the road dropping away into black canyons. When they entered New Mexico, traffic dwindled, towns fell into sleep, and the radio left off the Beatles and Stones hits and slid into static. They crawled alone across the country, dream-like time unmarked except for the illuminated clock set in the dashboard. 11:39. Nancy and Greg were asleep, her head on a pillow in the lap of her lover, phantoms at Gemma’s back.

12:07. She rattled with worries she couldn’t speak. What if someone found out and told her parents? Or Madame, her director, who lectured dancers about technique, but also about the imperative of representing the company with excellent behavior, no drunkenness, no carousing on the street. Sex before marriage unmentioned, but understood to be taboo. Abortions? God no, Madame was Catholic. Besides, they were against the law. Madame could punish her by taking away her solo, even her job. If that happened, she might as well have married Stefan when he asked and had a normal life. The word normal constricted Gemma’s breathing, crumpling diapers and book clubs and shopping into her chest. She pushed away little boys with their bats and frogs, little girls playing hopscotch. First comes love, then comes marriage, then comes baby…No, not for her. Again she hummed Tchaikovsky, imagined joyous leaps in the spotlight.

No one she knew had done what she was doing. In the way she was doing it. She’d seen girls drop out of school or return after five months “at a cousin’s”; a couple in her high school married hours after graduation; the girl had given up a scholarship. What were their lives like now? She imagined housewives and mothers, secretaries and teachers, night school and exhaustion. Dreams pushed away or forgotten. Dancers had a too-short career, no time for babies, and Gemma was on her way to becoming a true ballerina, something rare, like a perfect crystal (she ignored the sweat, pain, stage fright).

Ballet jobs were also rare: her mental list of professional companies stalled at eleven. At the audition for the newly professional Rocky Mountain Ballet, she’d danced among forty-two girls who pushed her aside with their fast turns and beautiful adagio. She hovered unnoticed at the back until, with a spurt of bravado, she forced herself front where she bloomed along the music to become the one Madame wanted.

The moon had long gone down. Wind rose, slapping the car; her stomach lurched and spun. Maybe her body had gotten the message, she’d have a miscarriage, and they could turn around. But no, she was simply car sick. She ate a cracker. 12:44. She nudged Stefan. “You okay? Awake?”

“I’m fine.”

“You could ask Greg to drive.”

“My car, my responsibility.”

To hear him say it was like holding hands, like running her cheek along his. “Both of us.”

He smiled in the clock’s faint light. “Don’t worry. That thought is engraved here.” He tapped his head. “Go to sleep.”

“Do you want music?”

“Look out the window.” He gestured at the black. “Only silence.”

She stroked his arm, sagged against the door, and plunged into dreams. The rushing air turned into applause. Even in her sleep, she knew the dance itself was more important than bows, but she was pushed in front of the curtain wearing the green tutu with the glittering bodice and the audience cheered.

#

At 4:30 Stefan pulled into an oversized gas station, startling in its light. Rows of parked semis crowded the lot, a herd of giant beasts. Greg went to the all-night café for coffee; Nancy and Gemma waited outside the single, occupied restroom.

“Gotta go, gotta go. Hurry up in there.” Nancy gripped her jacket and paced. “Emergency, emergency.” Her feet scraped the gravel. “Ya think the baby makes me need to pee so hard? I heard something about that.”

“Maybe.” Gemma wondered how far along Nancy was, but decided not to ask. “You and your boyfriend slept pretty good.”

“Boyfriend?” Nancy stopped with a soft whistle. “Wow. My brother. The goddamn boyfriend, if you wanna call him that, wouldn’t come. Even when Greg broke his nose.”

Across the lot, Greg handed a cup of coffee to Stefan who set it on top of the car and arched his back, stretching, face bleached in the light. Behind them, the great trucks slumbered.

“Once. Just once we do it. Me holding out for months ’cause everyone says it’s wrong, so when I give in, of course this happens. Boyfriend wants to marry. It’s not love, he says, but he wants to avoid mortal sin. How about mortal poverty?” Nancy stood with her legs crossed, jiggling. “Okay, okay, I get it. Church says it’s murder. So have it and give it away. Perfect. When all’s done you start fresh.” She began pacing again. “But meanwhile, goodbye job. Pregnant waitress, balancing plates on her stomach. I don’t think so.” She stopped in front of Gemma, almost yelling in her face. “I’m twenty fucking two. Kids? Marriage? Later, when I’m rich.” She laughed loudly and Gemma flinched. “Anyway, I’d of had it but how’d I feed it?”

“Maybe your family could help?” Gemma pressed her lips together. Not her business really but they were women with the same problem.

Nancy snorted. “You tell yours?” She pounded on the door. “Come on, hurry up in there before I pee my pants.”

No way Gemma told her family. Those straight-laced insurance agents, sales reps, stay-at-home mothers, not a single divorce thought she was a virgin and didn’t like her career. A flaunting they said. Godless. You’re a young girl, too soon to decide your life. She imagined lectures and tears, heavy blame. In college none of this would have happened. Only fools thought that. College girls were tempted right and left, virginity lost in back seats, couples faking marriage to get birth control prescriptions. She hugged herself. We all give in to love.

“Why those bigwigs hafta make this so damn hard?” Nancy punctuated her words by whacking the door. “They don’t give a shit about me.” Whack. “Or my kid.” Whack.

Whoever was in the Ladies yelled, “Give me a break. I got my period.”

Nancy stopped pounding. “We’re all sluts to them. But if some rich guy’s daughter spreads her legs and oops? They’ve got dough. They fly to Sweden and fix everything up all legal-like and safe.”

The door to the bathroom opened and a uniformed waitress exited. Nancy pushed in and just before she slammed the door, called to the woman’s back, “Hope ya washed your hands.”

#

The clock read 5:17. Along the horizon a dusting of pink. Ahead lay El Paso’s great spread of lights. “The clinic doesn’t open until eight. Let’s eat breakfast here.” Practical Greg who’d bought coffee for Stefan and packed a pillow for Nancy. “That way we won’t have to exchange dollars for pesos.”

“Bet they take dollars, Greggy,” said Nancy.

Stefan, who could hardly keep his eyes open, managed to say, “I don’t think the girls should eat before an operation.”

Operation sent a waking shot through Gemma – this wasn’t the simple scrape she’d pictured, like clearing eggs from a frying pan. It implied anesthesia, a potential for pain. For loss. Ignoring Stefan’s advice, Gemma ate a cup of oatmeal, dousing it with sugar and milk, cradling the warmth in her hands, letting the sweetness melt the rock in her chest. Nancy drank hot tea; the men ate eggs and salsa. Revived but wary, they drove into Mexico.

The crossing over the Rio Grande reminded Gemma of waiting in the wings. Everything still to happen, stomach tumbling in knots, heart urging her forward.

On what seemed to be Juarez’ main avenue, crowded buildings and a jumble of signs, the street shouting in Spanish. Only Coca-Cola comprehensible. As if in a slow-motion Technicolor movie, they drove past slashing red awnings, a spatter people in jeans with hoodies pulled up against the morning chill, and women arranging sidewalk displays of bright piles of fruits and vegetables. From the backseat, Greg gave directions using a crackling paper map. They turned into a quiet street where the white adobe clinic vibrated in the early sun.

Vibrating herself, Gemma longed to leap from the car, her first time in a foreign country, and smell the oranges and peppers or buy a mango, a persimmon. To skip. To hide. But no, this had to be done. Her shoulders clenched, her knees shook, but she kept her face smooth. She’d insisted; Stefan mustn’t know how scared she was.

Inside the clinic was clean and smelled of bleach. A good sign. The waiting room, which resembled a cheap hotel lobby with its low plastic table and thin modern couch, was empty. A bad sign. Maybe no one came here because it was dangerous. Because the doctors…

“¿En qué puedo ayudarle?”

Gemma clutched Stefan. “I left the dictionary in the car.”

“They spoke English when I called.”

They did. Greg was already at the desk with the receptionist.

A young nurse took Gemma and Nancy by the elbow and before they could say goodbye to the men, pulled them down a hall. When Gemma called out, Stefan began to sing an aria they both loved: Nessun dorma, no one sleeps. Le stelle che tremano d’amore e di speranza. The stars tremble with love and hope. A river of comfort flowed from him, lapping at her ankles, then doors closed, the aria was interrupted, and the nurse lightly pushed them into a room with two small beds. A window set high in the wall. The morning light barely dusted the space, creating a calm like in the dance studio but without the drift of past movement or music. Women in this space sat and waited and prayed. Cried. Dry-eyed, Gemma changed into the hospital gown, then, because lying down was out of the question – Nessun dorma – sat on the thin mattress across from Nancy, who seemed to be meditating. Other, earlier women shadowed the room. They’d come here because they had too many kids or had been young and unlucky; because of laws back home and because love was too insistent to wait. She closed her eyes, remembering the heat that made waiting impossible. Stefan’s body sliding into hers. Even at this moment, she knew she’d do it again: clothes thrown on the floor, naked on the bed, cradling his weight between her open legs. She swore today wouldn’t erase that joy.

A nurse wearing a stiff white hat entered. “Eating?”

Gemma opened her hands. She’d left the apples in the car with the dictionary.

“Por favor.” The nurse pointed at Gemma. “Eating?”

“No eating,” Nancy raised her hand and the nurse nodded toward the hall where a gurney stood. A real hospital, Gemma thought. The nurse turned to her and held up three fingers. “Usted. Tres horas.”

Three hours to wait. Her nerves shot like fireworks in all directions, thumping her heart, sending fire along her ribs. To soothe herself, Gemma stood to stretch her muscles and tendons which ached from the long drive. The familiar exercises, done on days without class or rehearsal or if she was just plain stiff, took an hour and fifteen minutes and when she finished, she went to the wall and rose slowly on demi-pointe to look out the window at a lot filled with dried weeds. Under the thin gown, her body cooled. Any minute Nancy would be back with news about what to expect.

But Nancy didn’t appear. The building was mute. Gemma rubbed her stomach and imagined the red dot gone. The thought threw her into movement. She began sketching out her solo, no space to leap, but arms to be perfected, the tilt of her head, the epaulement of her shoulders. She hummed and played with timing, no need to match the girls on the left and the right as if she were still in the corps de ballet. As she worked through the piece, she was no longer alone in Mexico, but alone in the spotlight bursting her elan over the audience.

Stage crashed back into cell when the door crashed open and the nurse said, “Ahora.”

In the hall Gemma climbed on the gurney and counted ceiling tiles as she was rolled down the hall. Eight. Let it be all right. Nine, ten. Please. When she reached 53, the gurney whacked through a swinging door. Startled, Gemma blinked under the bright lights.

“Ah, the young lady who ate.”

Gemma almost laughed out loud. The doctor spoke English.

“We are going to sedate you.”

She tried to sit up, but he pressed her gently back. Her tension flowed around his hand, rising like water. “Are you sure it will work?” His warmth and surgical gloves encouraged her to trust him. “I have a dancer’s body. It reacts strangely.”

The man smiled. “When the nurse puts in the needle, count backwards from ten. I guarantee before you reach one, all will be black.”

She wanted to tell him that her body was important, not just for living, but for her work, her whole life, but the nurse put the needle in her wrist. She held her breath and started counting. At seven, the doctor was right.

#

Gemma’s cat sat on her face, pinning her to the bed, furring her eyes shut. C’mon Petrushka, move. She tried to push him away but couldn’t find her arms. His weight sent her back into darkness.

Awake again. Shivering. No blanket, only a white sheet piled with red roses. The scent of iron. She curled tighter into herself and slept.

A dazzle of light traced veins in her eyelids. She covered her face and the warmth on her fingers stirred her awake. Sun flared through the clean window and although shadows lurked under the narrow beds, the room glowed, the floor radiant. Slowly her blood began to move. She remembered the clinic, her fought-for decision.

On the bed opposite, Nancy slept, or…Gemma squinted at the broad back, the plaid shirt, then slid closer to the wall, cowering under the sheet as danger shifted in the shadows. “Who are you?” The sleeper stirred and rolled over. She almost screamed. Then, “Oh! Stefan.”

“I was exhausted after driving all night. The nurse let me in.” He rubbed his eyes, his hair. “How do you feel?”

She took inventory. Stomach, flat; tender when pressed, but no pain. Between her legs nothing. “Okay.” The sheet was splotched with blood, rusty and dried. She crumpled it away. Too intimate for Stefan to see, despite their naked nights, shared bodies, words, ambition. His lost baby in the stains. Hers. The thought made her dizzy and she lay back down. “Where’s Nancy?”

“She and Greg went to explore the town.”

Gemma, eyes closed, spoke through the desert that was her mouth. “Why didn’t you go too?”

“To be here when you woke up.”

Feeling very young, very cared for, she managed, “I’m glad,” and slept again.

#

The nurse sent them out onto the street at 5:00 and they waited by the car until Nancy and Greg arrived, giddy and narrating their afternoon: the walking, the bars, the tequila, lime, and salt. “We had a blast.”

“The doctor said you could drink?” Barely upright, Gemma leaned on Stefan.

“I have no idea.” Nancy shrugged. “I don’t understand Spanish.”

“Mine spoke English.”

“Lucky you, but so what? Buenos dios and under you go.” Nancy tossed her purse in the back seat. “You shoulda been there. Some crazy guitarist on the street, his fingers fast as crickets. Best I ever heard.”

“Tequila ears,” Greg said. “He was awful. Sweetie, you called the bartender a prince. Two drinks and you’re totally whacked.”

“One drink and a sleeping drug.” She laughed and shook her hair.

Nancy’s fairytale of the town, the bar, the guitar player contradicted the hard beds and the red that bloomed from Gemma’s body. She clung to the image of Stefan asleep in the shaft of light.

When they crossed back into El Paso, safe, she tried to enter the world of the solo but her inner stage remained empty, her life suspended. She hoped it would awaken later when she was fully alert, when the uneasy shadows were gone, when she stopped thinking about those women who were still searching as she had searched. They might not have her luck and their lives would shatter.

Texas quickly behind them, into New Mexico. The mountains reared and fell along the horizon, barely visible. In the back seat, Greg and Nancy giggled about tequila worms but Gemma and Stefan didn’t speak. Once she put her hand on his thigh; once he turned and raised his eyebrows. She nodded. He’d forgive her and they’d love each other as before. That left only Madame, the tiny cross, the sharp eyes. Please, don’t let her guess.

On into the night. An occasional tumbleweed rolled across the road, fleet as an animal. The half-scoop of moon spilled pale light, smoothing and softening the prairie on their left. On the right, the mountains wore a rim of stars.

Gemma whispered to Stefan, “I’m going to sleep now but when I wake, I’ll drive.” Against his protest she said, “You have to work tomorrow.”

She dreamed of a coyote bounding alongside the car. She joined it to leap in perfect grands jetés until the moon forced them to separate, leaving the coyote to howl on the road. Dream Gemma watched from the back window as the animal shrank away, howl morphing into half-yips.

Her mouth dropped open. She jerked awake. The moon rested on the edge of the mountains and Stefan was driving steadily, eyes gleaming in the light from the clock, 12:34. “Where are we?”

“Just passed Raton. Can you wake Nancy? Her whimpering creeps me out.”

The siblings were asleep, Greg sprawled upright with Nancy’s head on his lap as before. Gemma reached back and shook the girl. “Nancy. Wake up. You’re having a bad dream.”

Nancy stirred but instead of ceasing, her cries thickened. “Greg.” She thrashed a little. “Greggy, I hurt.”

Greg woke. “What’s up?”

“Nancy needs help. Do you have aspirin?”

“Sure.” He unzipped a bag and uncapped a thermos; Nancy continued to cry. The movement in the back seat, as well as the constant moaning, roused the darkness, the shadow women. Gemma rolled her neck to loosen the knots.

“Settle down back there.” Stefan’s knuckles were white in the thin light. “I’ve got to concentrate.”

“Nancy, does it help if you turn over?” More movement, then Greg bucked, crashing into Gemma’s seat. “Oh God.”

The force of his voice twisted Gemma towards where he hunched over his sister.

“She’s bleeding.” Greg’s voice was a croak. “I can feel it on the seat.”

No, no, no. With shaking hands, Gemma touched herself. The absorbent pad and her underwear were dry. Surely he was wrong.

“Turn on the light,” Greg gasped. “I need to see.”

Nancy’s bleating became a solid wail, an animal let loose in the car.

“Shut up!” Stefan was threading a convoy of semis. “Do you want to get us killed?”

“Nancy, please.” Greg flailed in the back seat. “Turn on the fucking light.”

In the sudden light, Nancy’s face, eyes like dried plums, mouth open as she clutched the pillow between her legs. “Aaaaaaaah.” Greg lifted her skirt. The pillow was streaked with blood. Smears on his hands, his shirt.

“Oh God.” He gagged. “Stop the car.” He slapped Stefan’s shoulders.

Gemma threw herself across the seatback, seized Greg’s arm. “Do you want to crash?” She scratched his arms, his neck until he fell into the corner, moaning, “Oh fuck, fuck.”

“Stopping won’t help.” Stefan pushed the old car up to 80. “We need a hospital.”

The moon had gone down. The void was lit only by the uncaring stars. The car shimmied and their headlights probed the white stitched road. A sign flew past, a shiny punch in the dark: fifteen miles to Trinidad. Nancy’s howls sirened them forward.

The Trinidad hospital was aghast with light. Nurses lifted Nancy and wheeled her away, Greg running alongside.

“What do we do now?” Gemma’s knees trembled.

“Wait,” said Stefan. “Pray.”

They sat in the waiting area. A baby on a lap crackled with a cough, a college kid exclaimed over a broken ankle, an old man held his wife’s age-spotted hand. Battered by the smell of antiseptic, blood, bodies, Gemma hummed softly. Stefan prayed, head down, hands braced on either side of the orange plastic chair. She knew he’d been raised in a church – she’d forgotten the domination – and that he prayed before he sang. She’d thought his prayer similar to her own rituals before performance, but now the concentration on his face and the deep bend in his neck revealed a strong faith. Had he prayed the night she insisted on the abortion? She didn’t know. She stopped humming: we had been wrong. This had been all her. She wanted to grab Stefan, to say she was sorry, but in so many ways it was too late. She needed to sort out her choice but her mind held a labyrinth of paths, known and unknown. She couldn’t travel down those of the future. A career, maybe stardom. Or failure through injury. Years in the corps – not enough stage presence to become a soloist. But when she stopped dancing for whatever reason? Grief, marriage, a regular job. A baby. She pretended the little one coughing across the way was hers, that she smoothed its forehead and whispered to the soft cheek. Her heart stayed cool. Only when she looked at Stefan did it warm.

Greg came out to say Nancy was in surgery. He fidgeted, covered his face and moaned through his fingers.

“Come on, buddy.” Stefan put a hand on his shoulder and steered him down a long hall.

Gemma sat very straight, offering posture against final disaster – she had nothing else. As they walked up and down, she breathed good wishes. Occasionally a siren flared and a gurney rushed past. They, all of them, doctors, patients, Nancy, Greg, and Stefan should be home, sleeping off Thanksgiving dinner, innocent, sated.

A doctor came into the hall and Greg grabbed Stefan’s forearm. Gemma could see the indents his fingers made as he listened. Slowly his grip loosened, then he dropped his hand. Gemma was on the edge of a sob when Stefan turned with a nod and made an ok sign. Her posture collapsed in a whoosh of relief.

Stefan spoke to Greg, handed him a crumple of dollars, pushed him to follow the doctor, then came to Gemma, exhausted, the edges of his body unraveling. “She’s going to live.” He rubbed his eyes. “They were so damn stupid, partying afterwards. Makes me furious.”

Gemma held him together with a hug. “Why’d she bleed?”

“A perforated something. I only half-listened. It hurt too much.”

“How long do we wait?” Internally, she gave up the Monday rehearsal, the solo even. Nancy had almost died.

“No need. Greg has a cousin here. I gave him some cash. They’re worse off than we are.” He leaned on Gemma as they walked to the car.

In the vast lot under the buzzing lights, she said, “What were you talking about as you went up and down the hall?”

“Fishing.” Stefan staggered slightly. “Stupid, fucking stupid.”

“You don’t fish.”

“He does.”

She’d always remember his kindness.

#

It was after 4:00 when they left the hospital. Gemma drove and Stefan slept beside her, the back being too stained, too sticky with near tragedy. The highway stretched sleekly toward home; the old car responded to her touch and she passed a semi in a blur, changing lanes smoothly at a nudge on the wheel. At first the clock and the arms of the headlights were the only light but at Pueblo the sky took on a luster, the underside of the clouds downy red as the sun spread pink on the face of the mountains.

Gemma worked through her body, tensing, releasing each muscle, flexing each joint. Slowly her feelings woke, relief and a slight pride: she’d bet everything, broken the law, kept her dream, her very self intact. There’d be no going back. On Monday in rehearsal, she’d own the difficult pirouette, she’d gamble and risk and power through. Madame would notice. She sat straighter, drove faster while Stefan slept against the window, his eyelashes a fringe of shadow on his cheek. Past the Air Force Academy, past Castle Rock. Her mind rested. There was only the road and the clarity of the risen sun.

They reached her apartment in full glorious day. A sky fit for cherubs, air fresh and clean. Stefan stirred when the car stopped and she waited for him in a cocoon of silence and after a bit he wakened, stretched, touched her knee. When she took his hand, he began to sing. His voice was fuzzy but Gemma recognized the aria from his senior performance, the night she’d sat in the audience, heart exploding at his beauty, thrilled to think he loved her. Un dì, felice, eterea: one happy ethereal day. Now, his song filled the car with flowers. Lilacs and iris. Misterioso, misterioso. A puff of tender peony. When he sang the end – Croce e delizia, delizia al cor, torture and delight to the heart – from deep inside the aria, her life emerged.

Terri Lewis has been accepted to the Sewanee Writers’ Conference and into juried workshops with Rebecca Makkai, Laura Van Den Berg, and Jill McCorkle. She was a finalist for The Jeffrey E. Smith Editors Prize (Nonfiction) and shortlisted for LitMag’s Virginia Woolf Award for Short Fiction. She has been published in Embark, Hippocampus, Denver Quarterly, and Chicago Quarterly Review among others. Her reviews for The Washington Independent Review of Books have been excerpted in LitHub.

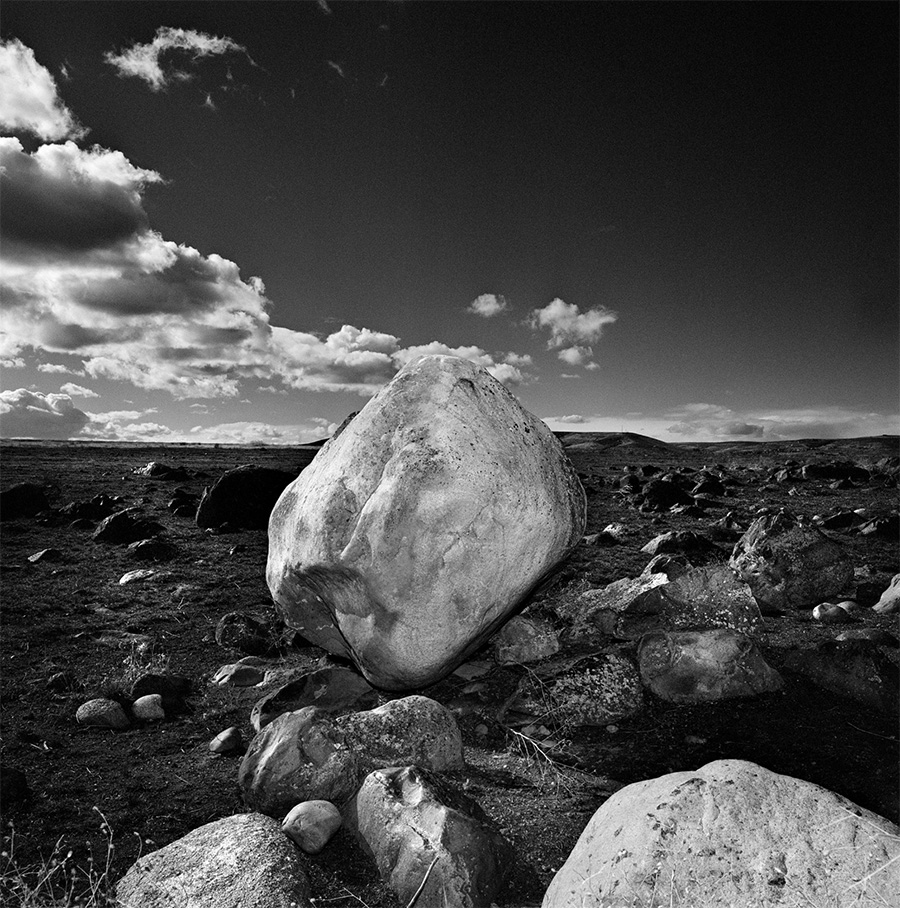

Over 40+ years as a successful award-winning commercial photographer, Jeff Corwin has taken photos out of a helicopter, in jungles, on oil rigs and an aircraft carrier. Assignments included portraits of famous faces and photos for well-known corporate clients. Corwin has turned his discerning eye to fine art photography. He still creates photographs grounded in design. Humble shapes, evocative lines. Eliminate clutter. Light when necessary. Repeat. His fine art photography has garnered awards, national and international museum exhibitions, gallery shows, work in permanent collections, features in numerous fine art publications, radio and newspaper interviews and representation by several contemporary galleries.

By Ciara Alfaro

By Katharine Beebe

By Craig Foster

By Elizabeth Cohen

By Bob Hicok

By Katey Linskey

By Michael Vargas

By Tolu Daniel

By Guarina Lopez

By Kristi D. Osorio

By Allen M. Price