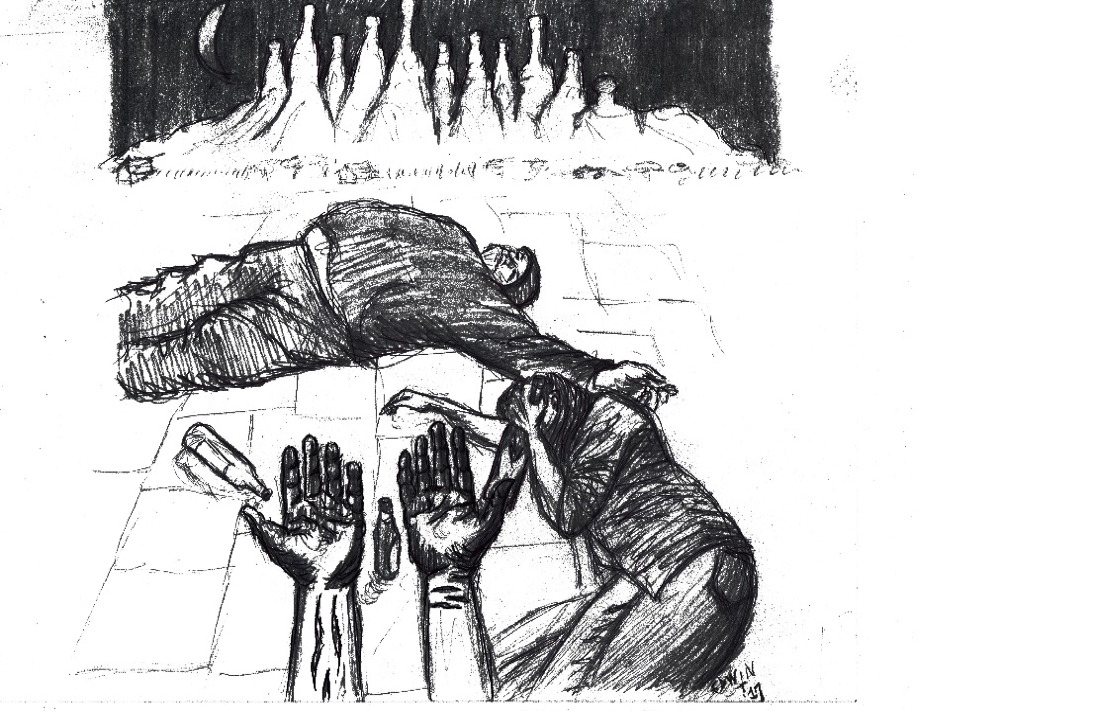

As a writer, but even more so as an indigenous writer, I’ve always been plagued by the pervasive image of the self-destructive, mentally ill, alcoholic writer. Think Hemingway, Faulkner, Edgar Allan Poe. And these are just a few on a list of American writers whose names are synonymous with alcoholism, mental illness, and deterioration. It doesn’t help that I’ve made this a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Anais Nin writes, “Great art was born of great terrors, great loneliness, great inhibitions, instabilities, and it always balances them.”

I’m not the first writer who’s been perplexed by this stereotype of the mentally ill, self-destructive writer. Maria Popova, of brainpickings.org, has explored the complex relationship between mental illness and creativity in her article “The Relationship between Creativity and Mental Illness” (2014). Decades before her, Thomas A. Dardis addressed a similar concern about the apparent connections between alcoholism and the writer in his 1989 book The Thirsty Muse: Alcohol and the American Writer. My questioning is only a more personal investigation of an ongoing, public conversation in the arts.

Simply being a writer who uses alcohol or who has a mental illness, or both, doesn’t necessarily condemn one. The connection is not so simple. Despite this, there is a stereotype that persists of the self-destructive writer: again, think Sylvia Plath, Virginia Woolf, and Anne Sexton. I can only offer you a voyeur’s look into my own experience to deconstruct this perceived connection between mental illness, alcohol use, and self-destructive behaviors.

My family’s legacy, both matrilineal and patrilineal, is alcoholism and self-destruction. I’ve inherited that legacy and continue to contribute to it. I started drinking when I got to college, around 18-years-old, and what initially started as social drinking with friends, quickly developed into drinking as a means of coping. I had chronic depression because of the traumas I’d suffered growing up in a home with intrafamilial violence and alcoholism, not to mention the everyday reality of living on a reservation where alcoholism, poverty, unemployment, early death, all forms of abuse, and drug abuse were, essentially, a contagion.

By age 21, I’d already been briefly hospitalized for a psychiatric stint facilitated by (not caused by) my drinking. I’d ended up cutting my forearm deeper than I’d intended and calling 911 after a brutal end-of-semester bender. My alcohol use has fluctuated over the years: after I married and had a child, it tapered off somewhat. I drank occasionally, but the state of my marriage induced another severe period of depression that lasted several years. I binge drank throughout this period.

Three years ago, I returned to academia to seriously pursue a career as a writer. Writing has ever been the only thing which fulfills me, this capacity to write which has no dependence on an external person or state. It was entirely internal, originating from my Self, and that recognition that I could fulfill my Self, rather than relying on social status, a husband or lover, or even a child, to do so, was poignant. Writing, however, was (and is) evasive in practice.

I couldn’t maintain my writing! I couldn’t force myself to write everyday as my professors told me I needed to in order to be serious about it! The greatest barrier to my writing has been my alcohol use, depression, and anxiety. The first couple of shots may help with breaking down the cognitive barriers (the internal critic) to allow me to write for a couple of hours, but long-term drinking has effected the quality of my writing. My writing doesn’t have the same precision that it does when I’m sober. The cycle is self-perpetuating: I become depressed over my inability to write, and I become anxious that I won’t be able to produce any good writing (much less consistently), which is what I must do if I want to write as a profession.

In spite of my mental illness and alcohol abuse, I’ve been able to write. The relationship between my ability to write and my mental illness and alcohol abuse is complex. My mental illness, or rather the experiences that led to the development of my mental illness and alcoholism, gives me material for writing, while simultaneously the act of writing itself is hampered by these same conditions.

Heather Johnson (aka Heather Johnson Lapahie) is a writer, teacher, mother, and lifelong student. She is an MFA student at the University of New Mexico and explores issues of marginalization, the individual identity, and voice in her writing.