Letter from the Editor

Anthony Yarbrough

What they don’t tell you about experiencing racism as a six-year-old Black boy is that when one of your white elementary school classmates calls you a racial slur, they’re telling you that you belong at the bottom of the racial hierarchy. And when you wake up the next day you expect to feel better, but you don’t. You open your eyes and feel the way you did the day before, only it’s today. Everything’s just like yesterday. And it is—underneath the brown skin that gives you your Blackness.

Some days you look in the mirror and see someone not like who they described, but someone who doesn’t see you as they do, and that reflection is the you who is you. Other days you look in the mirror and say something about yourself that’s in agreement with the racist insult your white classmate said, and that’s the you that’s not you. And maybe one day when you’re an adult that memory will be triggered, and that’s okay. That’s when you’ll cry and free your mind—tears from the fear that’s held you in that moment will release like the present, and make you realize how beautiful and amazing your Blackness is, and you’ll take back power of your feelings.

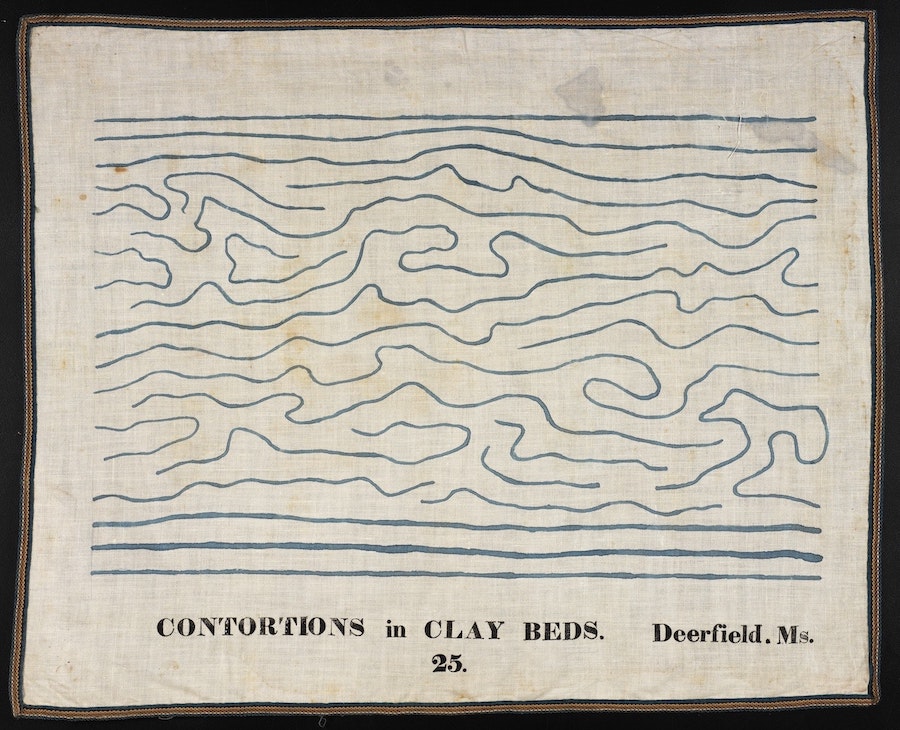

You’ll learn that the way you age is like the layers of a glacier: the lower layers are of continental origin while the upper are of snow accumulating, thickening similar to the way racism hardens the mind and body. And sometimes the layers splinter like the roots of a tree when lightning is loosened. You don’t always feel the trauma, not right away. It takes weeks, months, years, sometimes before the effects are felt. And when you do notice them, you try to move past, but they drop on you like a limb from a tree, fracturing your core being, exposing your suffering.

I wish I didn’t have a racist moment from my childhood. And I wish my brain knew how to un-brand it, because if my brain had known how, I wouldn’t have just stood there looking in a dazed, bewildered kind of way, struck solemn by the echo of my own hail as it rang unfamiliar through my interior when that white first-grade classmate called me the n word.

“Everyone,” our teacher, Mrs. Hickey said, sitting at her desk, “we’ve fifteen minutes before lunch. You can take the time to do what you want. Just please stay in your seats.”

I sat at my desk not having something to do, having no friends as school had started the previous week. I looked to the right of me at a blond, blue-eyed boy playing with Matchbox cars. He had the yellow Tonka truck I wanted but my then-divorced mother couldn’t afford to buy me, so I smiled and said, “Can I play?”

He stopped moving the cars and stared. A thousand-year-long minute passed before he said, “You look dirty.” Then he poked my cheek with his finger and wiped it on the desk. “You take a bath?”

Is my skin dirty? I recall thinking. I don’t wanna have soiled skin. I wanna look like him. I wasn’t born thinking why do I look dirty, or why does he look white? I didn’t think anything about white skin or brown skin. I wasn’t even aware of colorism, or racism. Unfortunately, I was alone in that.

“It’s my…I’m not…I was born…” I said in a small voice that I continue to use whenever I’m around white folk.

“My parents told me I’m not allowed to play with—”

“—Richard H. Clark!” Mrs. Hickey voiced angrily.

“Oooo,” the classroom said in a kind of chorus to a word I’d not heard before.

All of a sudden I felt sick. It wasn’t his words so much as the hostile, superior tone he used that made me feel awkwardly uncomfortable under the fear of such an imputation. I blushed from embarrassment; it was impossible that such a thought should not have sometimes entered my boy mind; but I had not self-interested views; and now I remained silent with too much good taste to disclaim.

“You apologize to Allen right now, young man.”

“But my parents—”

“—This instant!”

“My parents told me—”

“—I don’t care!”

Why me, why me, why me, but Mrs. Hickey was insistent. My embarrassment growing, I can’t remember if he atoned. I still can’t explain; the vision appears like unwoven time in a tapestry. The words must’ve not carried their proper significance. Or maybe the words were said in such strange tumult that they wouldn’t bear recording. All I know for certain is that in my eyes his face remains. And in my head I was screaming how long until the bell rings, how long until I can take off my brown skin and throw it in the trash like a torn breviary. Nevertheless, the boy’s apologetic remarks must not have answered their purpose because when the bell rang, Mrs. Hickey said, “Richard, follow me to the principal’s office.”

That was the last encounter Richard and I ever had. When I went home that day, I told my mother. She, Mrs. Hickey and the principal all had a meeting with Richard’s parents who said that that was how they were raising their children, so for the rest of the year, the school kept us away from each other. I wanted to run away, so far away like an autumn leaf blowing in the far away sky, so little you have to close your eyes to see it. Instead, I internalized the echelons of white supremacy, learned not to be presumptuous as to expect equal citizenship, and self-erased my Blackness. Whiteness was what America viewed as normal, born to relate rather than be related with. And so as I aged, I grew like an evergreen, my branches wandering forth in every direction, planting my roots deep, gripping the ground tight, enjoying the nourishment, but always wondering, waiting, fearing a white man would cut me down.

Allen M. Price won Solstice Literary Magazine’s 2023 Michael Steinberg Nonfiction Prize (chosen by Grace Talusan), and a finalist in Black Warrior Review’s 2023 Nonfiction Contest. He won Blue Earth Review’s 2022 Dog Daze Flash Creative Nonfiction Contest and Columbia Journal’s 2021 Nonfiction Winter Contest (chosen by Pamela Sneed). A 2024, 2023 and 2022 Pushcart Prize nominee, his work appears or forthcoming in Five Points, december, Cutthroat, Forge Literary Magazine, African Voices, Zone 3, Post Road, Sweet, North American Review, The Masters Review, Terrain.org, Shenandoah, Hobart, Transition, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, River Teeth, The Coachella Review, Pangyrus, and others. He has an MA from Emerson College.

By Ciara Alfaro

By Katharine Beebe

By Craig Foster

By Terri Lewis

By Elizabeth Cohen

By Bob Hicok

By Katey Linskey

By Michael Vargas