Letter from the Editor

By Anthony Yarbrough

Third place winner in the Spring 2024 Contest Issue judged by Sarah Gerard

When you’re fourteen and Christian, clean language is how you show your devotion to God. You’re the one who recommends a PG movie, skips the explicit songs, or corrects others’ language to “frick” or “crap” or “darn” or “shoot.” When I was fourteen, I wanted to be like Jesus, and I knew Jesus had never said the S-word or the F-word. I intended to do the same.

I’m still Christian, but I’m twenty now. And something’s changed.

My first realization was on a winter afternoon in Wyview Park Apartments. I had found my then-fiancé Isaac in his apartment, talking to his roommates about how he had finally said “shit.” He said the Holy Spirit told him to. He said there was no better word for that circumstance. And his roommate said, “I’m pretty sure the Holy Spirit didn’t tell you to swear.”

Isaac still says that it did. The context is he was talking to Finn Martin. Everybody at Wyview knew Finn. And we, as the church members, took on the responsibility of collectively preventing his suicide. So, when we found him with bleeding knuckles behind a door he had punched to splinters or curled up behind a bush with a razor blade and brand-new X’s in his forearm, or just staring at the horizon with nothing in his eyes except the beginnings of tears—we did our best. We gave hugs, we gave smiles, we gave reassurance—“Finn it’s okay and you don’t have to kill yourself and we all love you and, wow, you sure are going through some crap right now!”—to which Finn would say, “None of you get it, do you?”

When Isaac found Finn in his third-floor apartment, sitting in a corner with the blinds closed, he rushed to his side like everyone else and started reassuring him. But Finn wasn’t holding a knife. In fact, his cuts were scabs and were on their way to healing. But his cheeks were wet with tears, and his gaze avoided Isaac’s as if saying, “I’m just as alone as before you walked in here.” So, first, Isaac just sat next to him and listened to him cry. Eventually, he put his hand on Finn’s shoulder and said, “It’s okay and you don’t have to kill yourself and we all love you,” and then—

“Finn. I’m so sorry. You’re going through some serious shit right now.”

—to which Finn said, “Thanks, Isaac.”

It was only a second before he went back to crying. But he let Isaac put his arm around him, and he even nodded when Isaac said, “It’ll be okay.”

Because, for once, a sheltered, bright-eyed, Christian 22-year-old actually seemed to understand. He didn’t know much, but he knew it was bad enough to choke out a word he had refused to say for twenty-two years.

My second realization was in the passenger seat of my dad’s F-150 as Dad and I sang along to “Best of Green Day.” Dad was the man who had taught me not to swear in the first place, so it was especially surprising when he let “Boulevard of Broken Dreams” keep playing, even though it had an “E” next to the title.

This song was quieter, and Dad matched it, staring silently out the windshield with his hands gripped tightly around the steering wheel. It seemed strange until we finally got to the line where they said, “What’s fucked up.” I pretended I didn’t notice and kept swaying to the music, but Dad knew I noticed, and eventually, he said quietly:

“Sometimes it’s okay to say F-words. Sometimes you can’t just say ‘messed up.’”

“Messed up” used to be enough, back when all he knew about war was what was spewed from the mouths of politicians, influencers, and history teachers. The forbidden F-word is hardly warranted for “troops in Afghanistan,” “men and women fighting for our country,” or “the ultimate sacrifice.”

It wasn’t enough when he personally learned about all the shit that happens behind those buzzwords. And it wasn’t enough when he related fragments of the stories to me. He told me about honor guarding because “no man left behind” apparently applies to dead soldiers too. It was cryptic, but I learned that at some point, Dad had to sit alone in the dark with a dead body that was probably his friend. He told me about what land mines actually do and how soldiers would make it back to base but would die on the operating table because half of their bodies were splattered all over the battlefield. He told me about the inhuman voice blaring “rocket attack” and about how fireworks have never been the same since. He told me about how cold he felt when he realized that they only needed one deck of cards for game night—because now there were enough for everybody. “Messed up” was enough for me too, before I knew all that. Now, like Dad, I know it was fucked up.

Now, I don’t bother mentioning faceless soldiers or nameless wars or “messed up stuff that happens in Afghanistan.” None of those things exist. As long as I can’t relate every single detail of my father’s experience—the blood, the bombs, the smoke, the smell—“fucked up” will do.

At age twenty, clean language often seems more offensive than swear words. At age twenty, being like Jesus means dropping the smile for a moment to recognize what is actually happening. At age twenty, “crap” and “messed up” aren’t strong enough to hold the things I know about.

I can skip the R-rated movies all I want. But Dad couldn’t. Finn couldn’t. They didn’t get the choice to keep their lives PG. Their lives weren’t censored. We can use whatever Christian-friendly word we want, but at some point, I realized that Jesus would be wrong if he said Afghanistan was messed up. The neighborhood bully stealing someone’s bike is messed up. And he’d be wrong if he said Finn was going through crap. Getting assigned a 5-page essay on a Friday night is crap.

War is fucked up. So is suicide. And some people are going through shit.

Contest Judge Sarah Gerard on “When It’s Okay to Say Shit”:

This author’s imagery arrives on the page as forcefully as their language. The propulsion and brevity of this piece leave readers breathless by the end, thinking, What did I just read? And compelling us back to the beginning, to read it again. In just four pages, we move through suicidality, the brutality of war, the lasting effects of trauma, arriving at the same destination each time: the importance of language, the meaning it carries, the danger—the sin—of stealing its punch, and its divinity.

J.C. Graham is an undergraduate pursuing a degree in Creative Writing at Brigham Young University. While this is her first publication, she has big dreams for a career in writing. While she hopes to someday write novels full-time, she currently works as a screenwriter for BYUtv. In addition to writing, J.C. also loves playing Scott Joplin, acting in her local theatre troupe, and spending time with her husband.

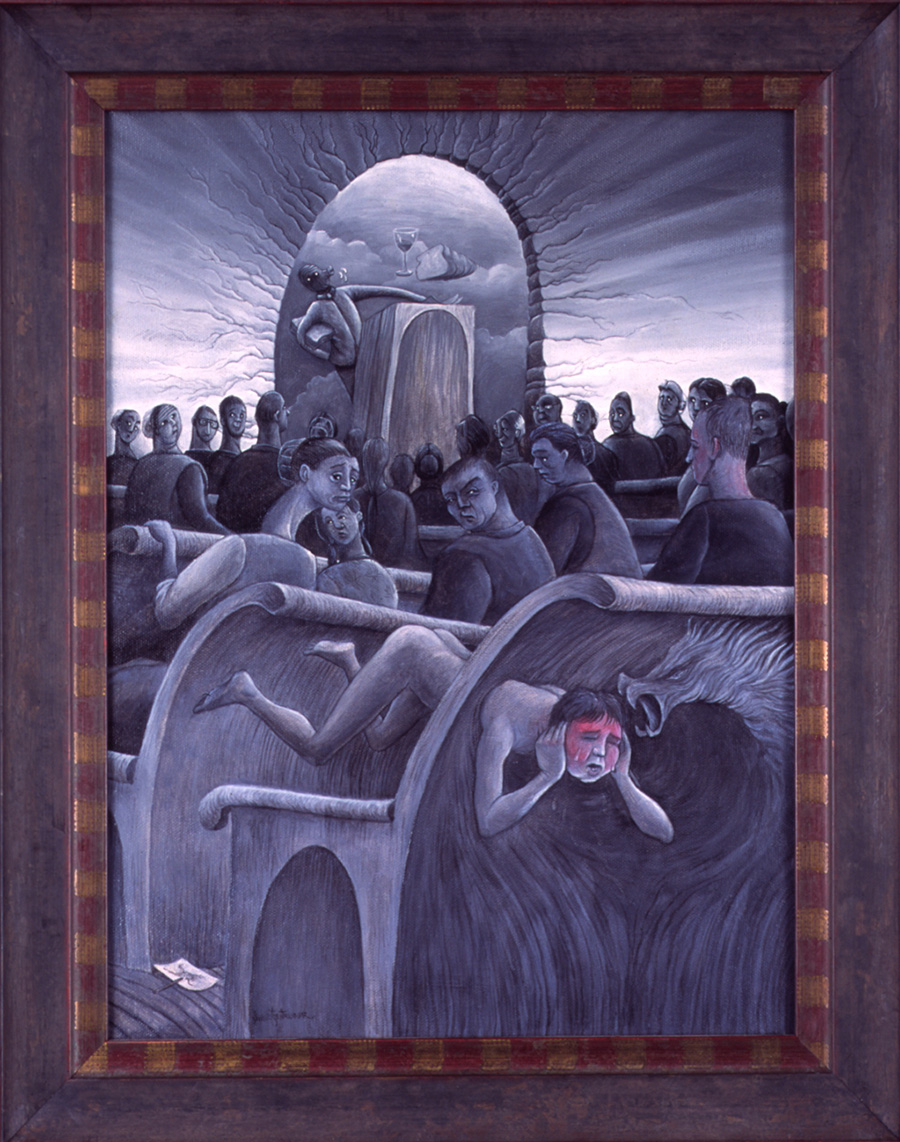

Don Swartzentruber grew up in an Amish Mennonite community in Sussex County, Delaware. He left his Old Order tradition to attend art school. After earning a Master of Fine Arts degree at Vermont College of Norwich University he decided to revisit his roots with a collection of paintings and drawings called “Pop-Mennonite.” The work created a stir among Mennonites, especially in Canada. Mennonite Weekly newspaper called it “Weird”. Disturbing. Bizarre.” Canadian Mennonite journal called it a “jarring juxtaposition of the sacred and the secular.” The work was exhibited at college galleries and museums. The original oil paintings are represented by Saatchi Art.

Squash Blossoms • Merridawn Duckler

By Anthony Yarbrough

By Noor Al-Samarrai

By Nancy Beauregard

By Harley Tonelli