“The Kármán line is the international boundary between the Earth and space. Due to inconsistencies in the Earth’s atmosphere this border is approximate. It marks the end of national boundaries and the beginning of what is known as / free space” (The Kármán Line, page 151).

In their debut collection The Kármán Line, Daisy Atterbury makes a spectrum of genre, blurring the boundaries between poetry and nonfiction, academic prose and prose poetry, biography and autobiography, un-charting a path for a multidimensional exploration of language, gender, and genre that is kaleidoscopic. The book is hyperreal and all-encompassing—academic, scientific, and artistic in its scope, incorporating equation, line break, stanza, and paragraph all as poetic elements, and employing citations and vignettes from scientific history as microcosms for a poetic whole. This flexing and warping of literary genre is an exercise in removing our illusions of control. Language itself is often beyond our control, as interpretations and methods of communication are vastly different even from one person to the next. There is also the problem of simply not having the words to define everything, including those things we don’t know yet.

The speaker grapples with these ideas about language and gradients while on a pilgrimage through New Mexico to Spaceport America, “driving towards some place someone once called empty.” They visit many places along the way, including the Very Large Array, Albuquerque, Jornada del Muerto, and the Trinity Site—the area of the U.S.’ first forays into nuclear weapons testing. As far as anyone knew at the time (and according to the fiction perpetuated by the popular film Oppenheimer), this land was empty. But it is only empty now “because someone once called it empty.” The land was actually inhabited by nearly half a million people in a 150-mile radius of the site, and these residents were given approximately 48 hours to vacate the area before the first bomb was tested. This perceived ‘emptiness’ is always necessary for the success of the colonial project. If we do not develop our language—in truth, ourselves—we are at risk of being empty, and this ‘emptiness’ is attractive to colonial entities as targets for erasure, for elimination. But The Kármán Line posits that language and the act of definition are not tools exclusive to colonial entities. They are within our own reach, if only we take the steps to resist colonial oppression and the fictions it perpetuates to fuel its war machine.

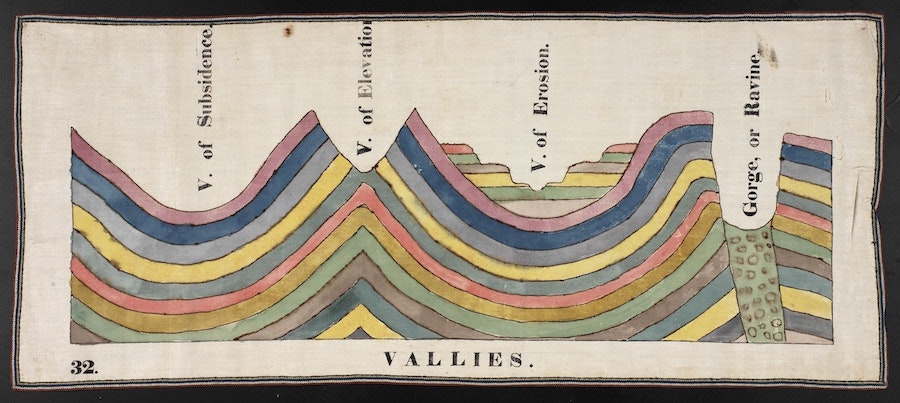

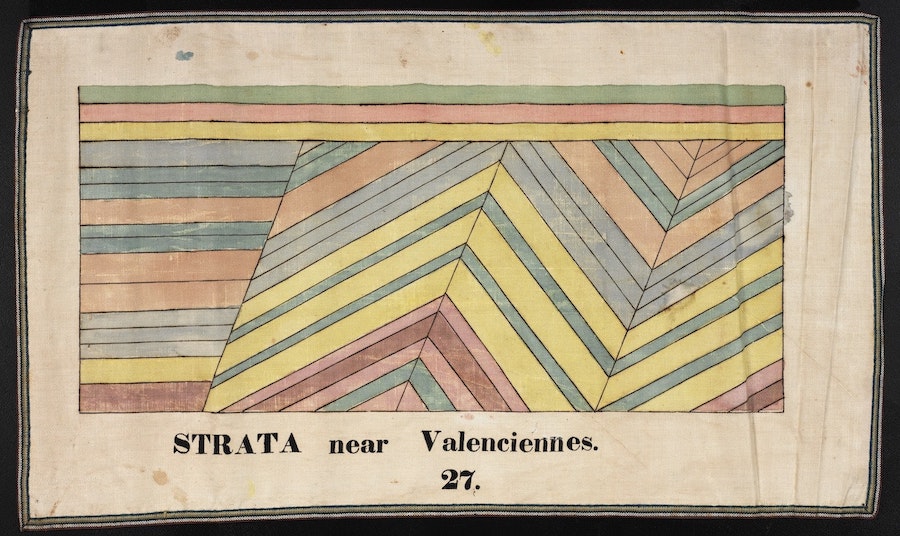

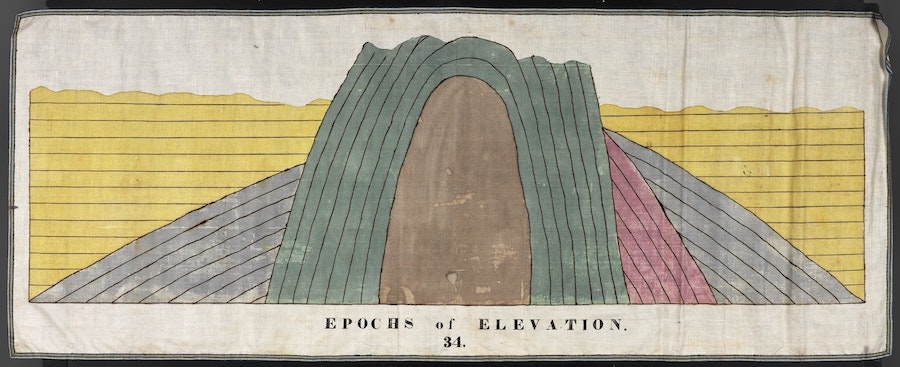

The opening poem, “places in no particular order,” is comprised of a list of places along an x, or horizontal, axis. This axis contrasts with the dividers of the book’s sections, which are also the strata of the atmosphere (troposphere – exosphere), along a y, or vertical, axis. At this intersection between Earth and space, we find an on-ramp to the highway of understanding—of land, space, gender, genre, profane and sacred, doubt and belief, and the boundaries between them, which are far less rigid than we have been led to believe.

Chaos recognizes no borders. Wildfire does not stop at an arbitrary boundary drawn on a map, nor the ground. Neither can the atmosphere be cordoned off and divided up for development. Gender cannot be completely understood or defined or categorized, just as our language or mathematics can only define things so much. These divisions are all far more nebulous than our current binary paradigm would allow us to believe. We exist in a world of duality and opposites forced upon us, and which we, in turn, enforce upon others. However, “the Kármán line is a gradation, and there’s a multitude of feeling beyond,” which is to say it is beyond our definition. Shifting. Intangible. Immeasurable. We can create a formula to measure it, but there are so many factors impacting its existence that it will always exist in a poetic grey area, in approximation. It is the same with gender, with genre, with the land.

I have always very much been a literature and humanities guy and not a math and science guy, but that never stopped me from being fascinated by nebulas or imaginary numbers. I had (and still have) a yearning for scientific knowledges I know must be there, that I believe are there because I have heard or seen some proof of their existence or because I heard a trusted expert speak about them, but that I lack the precise language for myself. I am particularly familiar with this space of knowing and not-knowing because I am transgender. For as long as I can remember, I have known something about myself that I didn’t always have the language to explain to anyone other than myself, and sometimes not even then. It took time to find the right language to explain how I instinctually understood myself. Even once I did, the process of understanding that language as it applied to myself took time as well. The boundary between one and the other is smudged to me; I exist in and along a spectrum of many things, not only my gender, but my heritage, my culture, the land I live on. Measurement, again, is a limiting fiction. The Kármán Line shows us that we can blur those lines if only we change our understanding, our perspective.

“Leonid’s Meteor Shower” grapples with many perspectives on space and the cosmos. There are so many variants of study, practice, experience, and identity of the stars—through astronomy, astrology, and our natural human curiosity. One lens cannot exist without the others; no one’s sense of the cosmos can exist without everyone else’s. In our language, we are reliant on one another, much like the planet’s make-up. Surface level ecosystems rely on one another. The uppermost or outer layers cannot exist without the lower or innermost layers. And, much like tumbling through free space in zero gravity, we can reorient ourselves to new ways of seeing and knowing simply by changing our perspective. The more we expand our capacity for language, the more we expand our capacity for understanding the world of grey area we inhabit.

Poetry is, perhaps, humanity’s greatest tool for the act of self-actualization and the repair of our home planet, and The Kármán Line is a living equation of language with the ability to blur our hand-drawn boundaries separating space, land, language, and self, giving us the tools to employ “betweenness as a new system of classification.”

Daisy Atterbury is a poet, essayist and scholar. Atterbury holds a full-time lectureship in the Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies Program and Department of American Studies at the University of New Mexico and recently curated the Living Room Series for Poetry at the Center for Contemporary Arts, Santa Fe. Daisy Atterbury’s The Kármán Line is now available for order through Rescue Press. https://rescuepress.co/author/daisy-atterbury