Letter from the Editor

By Anthony Yarbrough

Second place winner in the Spring 2024 Contest Issue judged by Jenn Givhan

Lucia’s parents ran an optometry business out of their house. The ground floor contained the waiting room with cases of glasses and an exam room that doubled as a shop. The first time Lucia’s father, Don Juan, led me into the back room to measure my vision, I stumbled through the exam, mixing up my Spanish vowels when he asked me to read the letters on a chart.

Picking the frames was no easier. Lucia stood next to me, her hand on the glass case that held the women’s frames. She pointed out the pair of red frames she wore. Lucia and her sisters got new frames every year. I walked across the room to look at the shapes of the men’s frames.

I wish I didn’t have to pick, I said.

I’ll pick for you, Lucia suggested, pulling first a pair of mahogany-colored women’s frames and then two pairs of thick black men’s frames that were too large for my face. I stood in front of the mirror in the women’s frames, trying to both look at myself and avoid my own gaze.

They are perfect, Lucia said smiling. I took the frames off my face and folded them back up.

I don’t even need to see, I said, but I went with the mahogany-colored frames because Lucia liked them.

Lucia’s older sister, Eunice, was in my grade at school and it wasn’t long before I began spending weekends at their house. We rode the bus downtown from the school and got off near Parque Central. I followed Eunice, Lucia, and Eunice’s twin sister, Yzabel, who was in Lucia’s grade, through the Calle Peatonal. The Calle Peatonal overwhelmed me with its sea of people moving in every direction. There were tables covered in clothing from the maquilas that could not be sold in the United States because of defects.

Even in my school uniform, I stood out on the street. I always kept my light-colored hair tied up in a bun, but there was no hiding my whiteness. I was visible. Lucia would keep her arm wrapped around me as we walked, as if she was trying to keep me present. Sometimes that worked.

My senior year Lucia and I became inseparable. I was spending almost every weekend at her house, riding the bus down after school on Friday, going to parties or watching MTV in Spanish, helping her family in the kitchen. And then on Sunday I would take a taxi and a bus back to my mom’s house in Loma Linda. My mom was busy doing research for her PhD, so she didn’t even seem to notice I was gone.

The weekend of Rafa’s party, Lucia and I turned and walked the other direction after we got off the bus. We had already told Eunice that we were going to buy guaro and cigarettes from the grocery store. Yzabel wouldn’t be going to the party because she had Friday night bible study with her mom’s prayer group.

After we turned around and saw that Eunice and Yzabel had disappeared into the crowd pulsing through the Calle Peatonal, Lucia put her arm tight around my waist and steered me in the direction of the small grocery. I expected Lucia’s arm to fall away from me when we entered the store, but she nodded to the uniformed guards at the entrance, her arm still tight around my waist; one of the guards let out a low whistle and held the door open for us. Because we were downtown the store was small and cramped. The tile was dirty, even though there was a worker moving a mop around the floor.

I hate the whistles, I said quietly to Lucia, my face red.

Gringa, no seas asi. Es lo que es. Lucia still held her arm tight around my middle and I really didn’t know what I was feeling. We walked to the liquor aisle and compared prices.

Tequila or guaro? Lucia asked.

Mmmm, you pick.

Lucia pulled a bottle of tequila off the shelf and then replaced it in favor of a cheaper brand. Vos tenes el pisto?

I smiled, Si.

We made our way up to the cash register, where Lucia asked for a blue pack of Belmont cigarettes. We were in our school uniforms—blue checked shirts, navy pants creased down the front. On the bus we had practiced what to say if we were carded; eighteen was the drinking age and we were both seventeen. Eunice should have come with me instead, as she had just turned eighteen, but it was rare to be carded, and I hung onto every moment next to Lucia.

I pulled out my wallet and handed over three hundred notes. The cashier looked at my blond hair, dishwater-brown really, but here it passed for blonde. She smiled as she counted the change back into my hand, and Lucia carried the plastic bag as we skipped out of the store.

How will we get to Rafa’s house? I asked Lucia. We had stopped to sit in Parque Central, the liquor stashed safely in my backpack. At one side of the park stood an old cathedral, one side opened up to the walking street that led to the optometry district where Lucia and her sisters lived, and a third side of the park was bordered by a taxi stand.

Once, when I first moved here, I had taken the bus to Parque Central with my mother, who seemed perpetually flustered when she was doing anything other than research in this country. She had worn hiking boots and shorts, and even though I had just moved here, I was already trying to fit in by wearing pants and not standing too close to my mother. If I spoke to her in public, I lowered my voice to a whisper. But my mother was the sort of person who had no intention of fitting in anywhere.

My mother had insisted on walking into the cathedral and standing before the candles burning in the alcove. It was dim, except for the light from the candles, and cooler in the church that outside in the square. The few other people inside seemed to have a purpose there. Mom, I had whispered, mortified by how even a whisper carried in such a quiet space. Let’s go outside, we look like tourists. But she didn’t hear me because she was moving towards the front of the church to look at the gold-plated altar mayor.

At the center of Parque Central stood an enormous ceiba tree. Its branches provided shade to a significant portion of the park, which took up an entire block. The trunk was so enormous, I once saw a group of primary school-aged kids linking hands to surround the tree. Cement benches surrounded the base of the tree.

We can take the bus to Rafa’s house, Lucia said. It’s getting home that will be the problem.

Who else will be there?

Rafa, por supuesto, and his sister, Glori. Ale, Gaby, Dani, no se quien mas.

Maybe Ale’s sister can drive us home? I suggested, reaching my arm behind me and placing my hand behind me on the bark of the ceiba tree. Despite the spines covering part of the trunk, the section of bark I held my hand on was smooth. Ale had tight curls and sat next to me in art class, one of the few classes I actually felt my body relax in.

Yes, gringa, but you can’t get too drunk if her sister is giving us a ride.

Ale’s sister was three years older, out of high school, working as a preschool teacher. She was also a good girl, unlike Ale. I looked at Lucia and smiled my widest bad smile. Lucia. She smiled back at me and pressed her hand on top of mine, so that I was pinned to the tree. I laughed and tried not to see anyone around us, but I could feel their eyes on me, and I could feel myself blushing.

Rafa’s house was halfway up the hill on the carretera to the school. We rode up on the city bus. I slid into the seat first, then Lucia slid in next to me, and Eunice sat on the outside. I lowered the bus window and leaned my forehead against the metal window frame. Over every bump I could feel Lucia’s thin hip press into mine. I listened to Eunice and Lucia talk quietly.

Rafa’s parents worked in the government, but I wasn’t sure exactly what they did. His house was surrounded by an eight-foot white wall topped with barbed wire. When we stepped off the bus into the dust along the road, Lucia grabbed my hand and we ran across the road. We stopped at the wall, unsure of what to do. Eunice knocked on the metal door and Lucia pushed the small buzzer next to the door at eye level. I stood just behind Lucia, her hand still tight around mine.

Lucia had insisted I change out of my uniform, even though my uniform felt safe to me. I wore dark blue jeans and a fitted black tee shirt. Lucia was wearing heels, jeans, and a white shirt with a black bra visible underneath. I wore my backpack with the tequila and cigarettes stashed inside.

We heard a click from the door latch, and the door pulled open. It was Rafa’s sister, Glori. She smiled at us. She was in Lucia’s grade and the two got along better than Eunice or I got along with Rafa. Glori had straightened her wavy hair so it looked much longer than normal. She tucked a strand behind her ear, running her fingers through it, emphasizing how straight it was. Behind her I could see the garden—flowers and fruit trees in the dusk light. I felt terribly out of place, like if Lucia didn’t tighten her grip on my hand I might fly away down the hill.

After my mother and I left the cathedral I noticed a plaque just inside the door. It told the history of the church, built in the mid-1700s to replace the original which had burned down. The temple was dedicated to the Archangel San Miguel.

Lucia dropped my hand at the door and kissed Glori on the cheek. Lucia walked through the gate. Eunice went through the same motions, kissing Glori and walking through the gate into the garden, and then it was my turn. I blushed and quickly moved towards Glori. She moved towards the kiss but stopped just short of my face, kissing the air. She said nothing to me but motioned us through the garden and into the house.

We walked through the sala—white walls, tile floors, and large paintings of women holding baskets of fruit—and out a back door onto a terra cotta tile patio where our classmates sat or stood holding beers and smoking. It was dark out already; the sun set around six each evening, because we were so close to the equator. Colored lights, like Christmas lights but with large round bulbs, were strung up around the outside of the patio.

Eunice and Lucia’s house was already asleep when we returned. Lucia carefully placed her key into the lock and opened the gate with a clang. Shhh, calladito, Eunice said. Lucia opened the front door with less noise. Ojala que esta dormida Yzabel. We crept up the curved staircase to the living room, which was open to the patio, open to the night sky.

But Yzabel was awake, sitting on the couch in the main living room upstairs. Dona Eunice sat next to her, one of the dogs on her lap. Dona Eunice’s long fingers ran through the dog’s fur. I tried to stifle a drunken giggle as I saw them sitting there with two church ladies. There was coffee on the table in front of them; wisps of smoke escaped from the mouth of each cup.

I leaned against Lucia and she grabbed my arm for stability. Gringa, calmate, she whispered, brushing my hair out of my face. I reached my hand up to my hair to twist it back into a bun.

Y mi cola? I asked Lucia, unsure if I was slurring my words. I felt undressed with my hair down around my face.

La perdiste bailando. Por ser bola. Lucia took hold of my hand and squeezed hard. I tried to hold my balance, one hand tangled in my hair and the other tight in Lucia’s. I did remember dancing, yes, but I did not remember dancing so hard I lost my hair tie.

Buenas noches, chicas, Dona Eunice said, moving the dog off of her lap. She motioned us over with a tilt of her head and a wave of her hand. The dog turned a circle on the couch next to her and then sat down, its face resting on its outstretched paws.

Que sueno que temenos, Mami, Eunice said because she was the soberest. Ya son las doce y media.

Dona Eunice had been praying for our safe return. She had been worried and so Dona Melba and Dona Ana had stayed to pray down the angels. And look, Dona Eunice said, the angels had returned us home safely. I felt rude not greeting everyone with a kiss, but I knew they would smell the tequila on my breath.

Vengan a saludar, Dona Eunice motioned again for us to come over to greet everyone. Eunice reluctantly walked over and gave first her mother and then the two church ladies a pico. I felt like I was going to vomit.

La gringa esta borracha. Lucia pulled me in the direction of her room. I giggled again, pulling her arm closer to my body. Lucia’s room had a door that opened up to the open patio and then a back door that opened up to the laundry area. There was a metal staircase that went up from the laundry area to the roof.

Let’s go up to the techo a fumar, I said as soon as Lucia shut her door behind me. She pulled me onto her bed, laughing.

You just saved my ass. Last time I came home drunk my mother made an appointment with the psychologist for me.

I stretched my arms up over my head and felt like I was floating in Lucia’s bedroom. I felt better when I was drunk, like somehow who I was inside matched up with the sensations of my body. Lucia stood up and pulled open a drawer of her dresser. She unzipped her jeans and stepped out of them, but I couldn’t keep my eyes on her, so I turned my head towards the wall.

Lucia’s walls were painted a garish purple and we had written things in black Sharpie all over them. I found the bat Lucia had drawn and the “Maria Juana was here” I had written one bored afternoon.

I closed my eyes and felt my fingers in Ale’s curls again. After drinking three beers and trying to keep up with everyone else dancing, I had moved towards Ale, who had been watching me all night. I felt Ale’s lips on mine again. Kissing her mouth had been such a surprise, and then I had heard some of the boys hissing, which made me want to pull away, but it seemed to excite Ale.

I opened my eyes to see Lucia watching me, with the same uncertain expression she had watched Ale kissing me at the party. She had already changed into a pair of silky pajama bottoms.

Do you still want to go up to the roof to smoke? She pulled the mostly empty pack of cigarettes out of my backpack. I pulled the lighter out of my pocket and handed it to her. She took my hand, and I pulled myself to my feet. My head had cleared just a little and I thought smoking a cigarette would sober me up even more.

We walked out the back door to the laundry area, then up the twisting metal staircase. Lucia put her hands on my waist to steady herself as she walked up behind me. It was like we were dancing, and I didn’t want to stop, but then my feet hit the roof.

The entire roof was flat. It was bordered by an iron railing and on one end stood the house’s cistern. Once, in the heat of the summer, we had laid out on the roof sunbathing and then opened the lid of the cistern to swim. I walked over to the railing and looked down the two stories into the patio. There were huge aloe vera plants, their plump bodies like dinosaurs struggling to get out of terra cotta pots.

Imagine jumping, I said to Lucia. She moved next to me so that her shoulder and hip were touching my shoulder and hip, which sent electric shocks up and down my body. I let my head tip onto her shoulder.

I imagine jumping some nights.

Do you think anyone has jumped from this roof before? I asked, lifting my head off Lucia’s shoulder to look at her face. Lucia’s face was lit by the streetlights below, and her hair blew in the breeze, dancing shadows on her face. Her hands gripped the iron railing tight, as if she might accidentally jump if she let go.

Yes. The previous owner told my father the story.

Tell me, Lucia! Even drunk I was eager for stories of other people’s pain. Do you think there is a ghost?

Ok, listen, this is how I heard the story. Lucia pulled out a cigarette and put it between my lips. She took the lighter and touched the flame to the end of my cigarette. I inhaled and listened as Lucia told me how her house had been a boarding house for students in the eighties who came to Ciudad Capital from the campos to study at the university. I imagined each room that opened up to the center patio housing a student. They were all young men at the boarding house because families in this country kept their daughters closer. Lucia told me that one night one of the students had too much to drink and jumped to his death from the roof.

Do you think a person would die if they jumped? It isn’t very far.

That’s the story, Lucia replied. We both looked over the railing and the tiled patio two stories below. Maybe it would kill a person, I thought.

I walked to the other edge of the roof, which overlooked the empty street below. Electric wires crisscrossed above the street at the same height as the roof. The tangle of wires reminded me of how I felt—impossible to sort out. Lucia came up behind me and I turned around to face her, my back against the iron fence. She looked even more beautiful in the dark. She put one arm around my waist and leaned into me.

Contest Judge Jenn Givhan on “On the Roof”:

The worldbuilding tethered me to these characters, and I longed to stay with them longer. This felt like the opening of a novel, in the best way. The nuanced gesturing in the last paragraph left me reeling on the precipice with the narrator.

Claire Robbins teaches at Kalamazoo Valley Community College and serves on the board of a youth arts collaborative. They have published short fiction, essays, and poetry in Nimrod, American Short Fiction, Passages North, River River, Harpur Palate, and elsewhere.

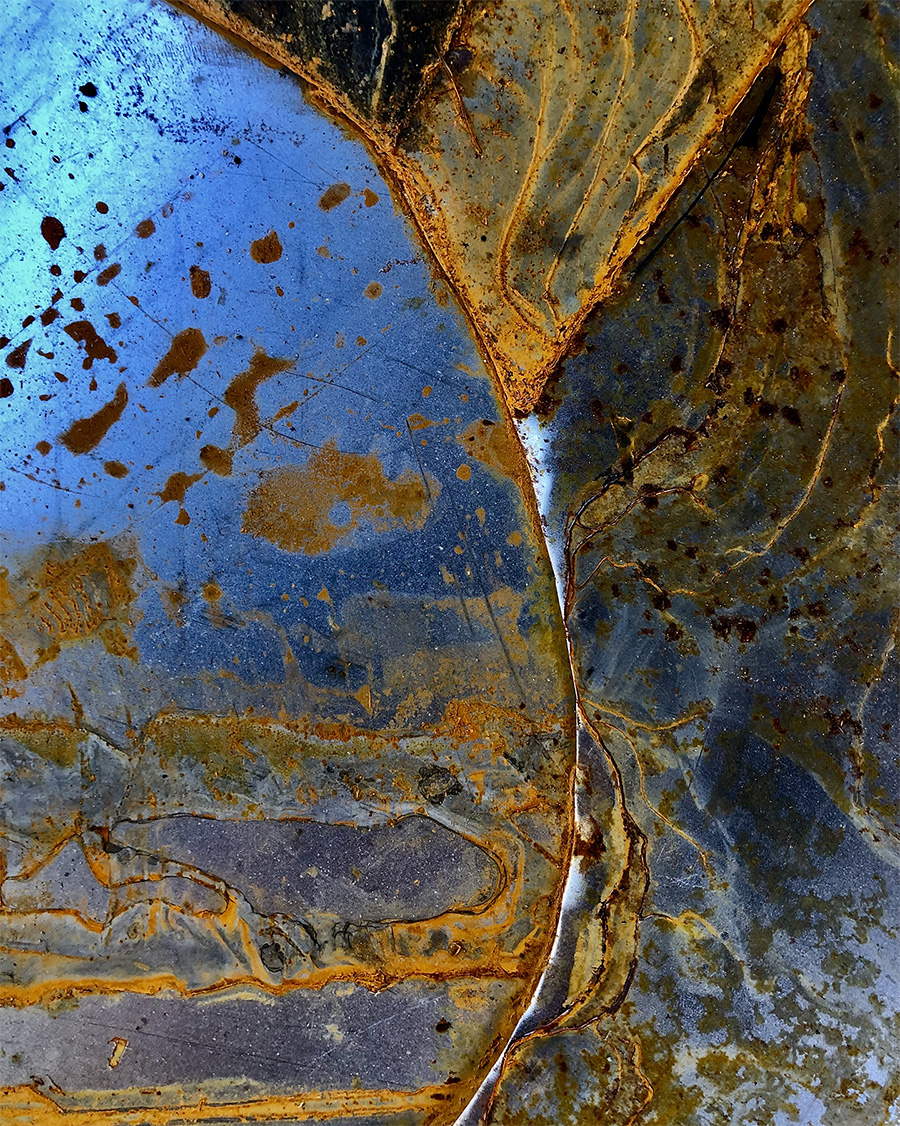

Matthew Fertel is an abstract photographer who seeks out beauty in the mundane. Small details get framed in ways that draw attention away from the actual object and focus on the shapes, textures, and colors, transforming them into abstract landscapes, figures, and faces. His goal is to use these out-ofcontext images to create compositions that encourage an implied narrative that is easily influenced by the viewer and is open to multiple interpretations.

Squash Blossoms • Merridawn Duckler

By Anthony Yarbrough

By Noor Al-Samarrai

By Nancy Beauregard

By Harley Tonelli

By Camille Louise Goering

By Monika Dziamka

By J.C. Graham