Letter from the Editor

By Anthony Yarbrough

Second place winner in the Spring 2024 Contest Issue judged by Sarah Gerard

Drip. Drip. Plink! Drip. Drip. Plink! The water beads together and falls from the wet clothing hanging on the plastic lines above me, which stretch from wall to wall and span the length of the bathtub I am soaking in inside my grandmother’s tiny bathroom. This is how laundry is dried here when the outside temperature is no good, and the clothing can’t be strung up on the balcony to dry. There is no dryer in this fifth-floor apartment, and there are no general laundry facilities in the apartment building at all or anywhere else within a convenient distance here in this industrial city of Sosnowiec, Poland. There is a washing machine in this apartment, but even as a child, I know it is only for special occasions—such as now when family is visiting—because it is considered a wasteful thing, a lazy and expensive use of water to just be taken advantage of whenever. Certainly, my grandma says in Polish, she will not use the machine merely for herself, she who has been living here alone and managing just fine for at least two decades since my grandfather’s death. Anyway, it’s too loud, she adds. As heavy as it is, it rattles the apartment walls when it’s on and makes the bathroom floor shake. Maybe she said this part, too, or maybe the idea came to me on its own, but sometimes during those visits, I would worry: What if the washer were to split the floor open and crash through to the apartment below?

The washing machine, squat like a block of concrete, sits beside the tub and takes up a major portion of the already limited floor space. At least it also provides a countertop for toiletries and towels when it’s not roaring through its one and only cycle, coughing dirty water through a tube that has to be attached and then positioned manually, with one end draped into the tub. Clothing can be washed, or bodies, but not both at the same time. No guarantees on whether the water will be hot in either case or how long that heat will last.

Most of the drops dripping down on me merge musically into my tepid bath, but some land with a soft thud that’s almost silent against my head and shoulders. Pum. Pum. Some fall on the island peaks that are my knees rising from my make-believe bathwater ocean. I am around twelve years old, and the hair on my legs is growing darker. I imagine the raining jeans and blouses above me are the sources of a tropical storm, hanging heavy overhead and blocking out most of the fluorescent sun. Unused plastic clothespins become boats, this one yellow, this one green, circling the islands. A rounded bar of soap acts as an airplane, flying passengers from the distant land atop the washing machine to Knee Islands, home to the steepest water slides in the world. Weeeeeeeeeee splash! Adults move on task in this one and only bathroom, quickly in and out, but because I am a child, I’m allowed to linger. Drip. Drip. Plink! Some drops hit the metal faucet beyond my feet, creating a high-pitched, tinny sound.

Above the faucet is what looks like an outdoor utility box but with a valve for gas and a turn dial showing power levels. This box’s tubing does not need to be maneuvered; it disappears into the wall all by itself. This is the bathroom’s water heater, its smaller cousin living in the kitchen, heating water on an as-needed basis. A little window on the bottom corner of the box shows a tiny flickering blue light. The pilot light. The adults have learned to trust me by now to turn the dial myself. Clickclickclickclick, FFFFRRRrrrrooooooommmm: The sound of the gas meeting the flame, the first step to luxurious bathing. It’s not unlike the sound a gas stove makes, taking a few seconds to catch. I like to make the flame big, anticipating the burst. In my imaginary bathtub kingdom, the box represents a rocky, barren mountain that towers high above the bathwater ocean and the land formations of my body. It rises so high that it nearly touches the storm clouds, and the little window where I can see the flame is actually an opening into a magical cave hollowed out by fire and lava where legendary swords are forged. This is the year of reading the Redwall books by Brian Jacques, a sweeping fantasy series in which mice, hares, badgers, otters, and other creatures go on great adventures, fight with swords, sip strawberry cordial, bake savory root vegetable pies, and sing songs of remembrance for the ones they’ve lost. A paperback copy of Salamandastron had traveled with me overseas this summer for my stay with my grandma. I read about the titular extinct volcano and its ruler, the badger lord Urthstripe The Strong, while my grandma kept me continuously supplied with a bowl of cherries, a plate of cookies, or some other treat. Sometimes, I’d read my book during my bath.

Drip. Drip. Plink! FFFFRRRrrrrroooooooommmmm. Among these sounds, I can hear the movements of my family just outside the bathroom, closing doors and putting away dishes in the kitchen. Someone, probably my father, is flipping through the TV channels to get to the evening news. The cheerful voices from the commercials, then the serious voice of a male anchor. I like these sounds, and I will them silently, to continue. They are a sort of soundtrack to this generally happy and predictable family life. To this concert, I add my own: Neeeeeooooooommm goes the soap plane as it soars above the land. Tuk tuk tuk go the colorful boats around the islands. This bathroom carries sound; someone upstairs has flushed his toilet. It’s amusing to me to visualize bathrooms stacked on top of each other, floor after floor, a tower of toilets lined up neatly and connected by the same pipes. How many people sit on the toilet at the exact same time? The idea doesn’t bother me. It’s just important for this bathroom to be noisy while I’m in it. I don’t like to be here when it’s quiet. If it gets too quiet, there’s a chance I can hear the screaming of the woman who is dying slowly in the apartment below.

***

At two different time periods in my life, I’ve heard the sounds of people dying. They are raw, primeval noises, unmistakable, though they can come in different forms. It can be a guttural expulsion, starting low and rumbling faster into a louder cry. Or it can be a series of moans varying in pitch and duration. One piercing shriek. Or something like a howl. Or something like a whimper. Not unlike a sound that escapes us in a moment of injury, grief, or fear. Though they can be different, these sounds share the quality that they seem to come from some deeper core within the human body, beyond describable emotion. They are void of any self-consciousness or agenda. They just happen, uncontrollable, without an aim to gain attention or to evoke any kind of response—similar to sounds that erupt from within us in our purest moments of surprise or joy, or during sex or childbirth, when a person might not even hear the sound itself, much less realize where the sound is coming from.

The first time I heard the sounds, they came from a woman from my grandma’s downstairs neighbor. I’ll call her Mrs. L. The second time, decades later, they came from a man in Upstate New York. I’ll call him Mr. W. Despite their genders and differences in age—Mrs. L in her forties and Mr. W in his seventies—there was something similar in those sounds, and both times I heard them, they shocked me. When I think about those sounds now, I feel the same as when I did then, a tightness seizing in my lungs, forgetting briefly how to breathe. A sour surge in my stomach. My eyes focus on whatever happens right then to be in my line of sight—a single strand of wet hair on the bathtub’s edge, looking like the outline of a lobster claw or the rusting metal clasp on a capsized clothespin. I notice, too, how fast my heart is beating, as though in arrogant rebellion. This is another type of language between bodies. Some body nearby is dying, so mine must test its functions. All systems go? Check, check, check. Maybe this is why people sometimes burst out laughing when they’re at a funeral.

***

Mrs. L was in her early forties, and she had multiple sclerosis. She was married to a scientist, and they had a son, whom she had walked to and from school every day when she was still able to walk. She’d been very elegant, my grandma would say, always in heels and carrying a handbag, even on those school walks, even if she just needed to go quickly to the store. In the winter, she wore fur. Her hair had been dark and full and wavy.

If I had met her before she’d fallen ill, I can’t remember. I never saw any photographs of her. I learned about her mainly through my grandma. The disease ravaged Mrs. L’s body quickly. Each summer I came to visit, she was worse. Within three or four years, she had become home-bound, then bed-bound. At some point, her bed became the fold-out couch in her living room so that, as my grandma would explain, she could see more through the windows and get more sunshine and fresh air. Her husband and son, involved as they were with cooking and cleaning, got help from a professional caretaker who came regularly to their apartment. My grandma, already retired at that time, became her caretaker, too, as work, school, and other schedule conflicts increasingly came up for Mrs. L’s family. Grandma picked up groceries, cooked for her, and fed her. She tidied up the house. She helped change Mrs. L out of her incontinence undergarments and got her bathed. Mrs. L’s body further shrank and twisted on itself, trapping her inside.

***

MS is a chronic disease of the central nervous system. Symptoms like blurred vision, slurred speech, poor balance and coordination, difficulty with memory and concentration, and numbness or even paralysis can come and go or worsen over time. It is unpredictable in that there does not seem to be any clear genetic or environmental cause, though people who smoke, are deficient in Vitamin D, and have autoimmune issues may be more prone to it. There are four types of MS, but in any case, women are more likely than men to get the disease, and it usually appears within the age range of twenty to fifty. Though there currently is no cure, early diagnosis, medication, and physical therapy help most people with MS live, and live well, into old age.

I learned about MS in detail when, in my mid-twenties, I found out that a male friend of mine, the same age as me, had been diagnosed with the disease. Immediately, I thought of Mrs. L and was horrified, my imagination uncontrolled. Not knowing what else to do, I read what I could about MS, and the reality of what an MS diagnosis means today calmed me down. I can’t be sure of the medical details surrounding Mrs. L, but knowledge about MS in the early 1990s and the medical treatment available to her then was very limited. It’s also possible that the particular type of MS she had was especially egregious.

When I ask my grandma about Mrs. L now, twenty years later, it’s clear I am stoking embers. I suspect she is among a group of people who wonder if they could have done things differently for her. We are sitting at her dining table, and she’s tugging at some crumbs caught in the white tablecloth. My grandma winces, then looks away. That’s how it is sometimes in life, she says and shakes her head: Terrible, terrible. She never speaks in detail. Sometimes, she’ll add one of her favorite sayings: Starość nie radość. Old age is nothing joyful. She changes the subject. That it’s taken me so long to ask her or even vocalize my own memories about Mrs. L tells me, too, I think, how much her sounds have haunted me. I cannot bring myself to seek out her husband or her son. What would I say? Do they already know what I might tell them?

Do you know that when I was a kid, I heard her crying, shouting, fighting against her own body’s betrayal? The sounds she made rose up like smoke into the bathroom and changed the way I breathed, with notes of things I could not name then at that age. I could only make sense of her sounds and their effect on me with words I knew: Alarm and fear and grief and pity, and something else, disgust. And then—guilt and shame for feeling like I could not fully enjoy my bath time, for wishing sometimes as I toed the faucet with my strong, working legs or as I passed a soapy washcloth down my healthy spine that her sounds would just … completely … stop. Do you know that after her sounds did stop, when I was an adult and taking a bath in that same small tub, there were times when I thought that I could still hear her?

I would apologize to them for thinking so much of myself. For not considering that they and others in this apartment building had also heard her as she had journeyed to her death. That they had surely heard other sounds from her at some point, beautiful and terrible, that I had never heard. And that just because I had never heard either the husband or the son crying or screaming themselves, it didn’t mean that their crying and screaming hadn’t happened. Their silence was not empty of emotion. Volume does not have to be an indicator of pain.

***

Shortly before she died, sometime around my fourteenth birthday, I saw Mrs. L. I had desperately not wanted to. I’d been reading a new novel in the living room, warming in the summer sunshine passing through the balcony windows, undoubtedly with some snack my grandma had left me. My grandma had gone downstairs to tend to Mrs. L. The rest of my family was out somewhere; I can’t remember where and why I didn’t go with them. After some time, my grandma came urgently back upstairs and, as though I was about to be late for an appointment, she rushed me up from my seat, insisting I needed to meet Mrs. L and that now was the exact right time to do so. Thinking back to this moment now, I believe she wanted to take advantage of the fact that I was home alone, without my parents to potentially intervene. Ibelieve she also knew this might be my last chance to see Mrs. L, as close as she was to death then. At first, I was too surprised by my grandma’s demand to be reluctant, but then I recoiled from her reaching hand and wanted desperately to run away from her. I said out loud—at last—that I was scared of Mrs. L. It’s possible my grandma tried to slap me then.

Moments later, and feeling ashamed, I followed my grandma down one flight of stairs and into the apartment below. My grandma instructed me to close the front door behind us quietly. She then gestured for me to follow her through the short and well-lit hallway, and we walked past the sunny kitchen on the left and into the dark living room. The layout of the apartment was the same as upstairs, I noticed, startled. As my eyes adjusted to the dusky space, the hammering of my heart grew louder in my ears. Thud thud thud thud thud thud. The balcony door was closed, and the curtains were drawn. No lamp was turned on, just a dim, filtered light came into the room from outside. It felt as though I’d entered something like a den. Or perhaps a mysterious cave in a barren mountain or someplace deep inside an extinct volcano. As I had been exposed to sounds during those summers in Poland that I had previously not known, so, too, at that moment, I was getting introduced to smells that I had never before smelled. Do all people who are dying smell the same? I’ve heard nurse and doctor friends say that they do. I’ve also heard that people who are close to death share a certain look in their eyes, a look that’s been described as distant, or as if some little fire has been extinguished and all that remains is a slowly curling stream of smoke. I took a few slow, small steps forward as though drawn under a spell.

To my left, against one wall, there was a bed, and in the middle of it, with her back to us, lay Mrs. L, the wife and mother and neighbor in the apartment on the fourth floor. Her skin, which I remember being gray, though it could have looked that way because of the pale light, sunk darkly around her exposed shoulders and into her cheek. We walked up to the middle edge of the bed. I looked down at her, just a few feet in front of me. Her eyes were open, blinking slowly toward the wall, and her mouth was open, but she did not move when we approached. She seemed tightly coiled, but the rise and fall of her abdomen was gentle. Through the thin sheet that draped over her body, I could see that she lay curled up, tiny, made more compact by her limbs that folded into themselves at severe angles. It looked as if one foot was pressed to the back of one leg and that the upper portions of her legs, as well as her arms, were the same size as their lower counterparts. Her hair seemed shrunken, too, short but matted unevenly against her skull. I say skull because here is where I get closer to confessing how she really looked, though I’m afraid to say it for myself and for the people who knew her. And for the people living with MS today, including my friend, who by all accounts is healthy and living well. In truth, she looked like some ashen, gnarled skeleton creature hiding in the dark, and I was terrified of her. Had I wanted to run away again, there’d be no chance. I stood locked in that living room, unable to do anything but stare.

A thought came to me later, remembering the way her hair looked then and how I’d heard my grandma describe it before Mrs. L became ill: dark and full and wavy. I don’t know if it had fallen out and had been trying to grow back when I saw her on that day or if it had been cut like that on purpose. It occurred to me that I did not know which way was worse, whether this symbol of her vitality and elegance had been lost—and that her little bit of hair showed some last heroic, magnificent, but utterly hopeless push to come back to life—or whether it had been forcefully cut away, with her unable to resist or even to protest, for the convenience of the caretaker.

My grandma spoke with exaggerated cheer, too loudly. Look who I’ve brought to see you, dear! It’s my granddaughter, you remember? You’ve heard so much about her!

Who knows what this woman knew about me. Had she ever heard of Brian Jacques or Salamandastron? Had she ever heard me through the bathroom? Suddenly feeling hot and embarrassed, I thought of the moments when I’d made my playful sounds with toys during my bath time or whenever I’d sung a Spice Girls song into the bathroom mirror.

I felt the weight of my grandma’s hand on my shoulder as she moved me even closer to the bed. She motioned for me to sit down. That’s right, introduce yourself, say hello! She pushed my arm forward to shake the woman’s right hand, which was bunched between her bare right shoulder and her right ear as though it were a nocturnal flower opening from her collarbone. I must have stammered out some greeting and then managed awkwardly to grasp a few of her fingertips with my own, holding them just for a moment. I don’t know if her eyes rolled then in my direction because I focused only on her hand, but at my touch, I remember that she made a noise that was like a breathy gasp, though it did not seem like I had startled her.

We didn’t stay much longer there, my grandma and I. Nor did Mrs. L in that apartment. Later that day, I don’t think I went back to reading, but I cannot remember how the rest of the afternoon passed or what any of the immediate days were like that followed. I don’t believe my parents knew of my visit until a decade or more later when it was mentioned in passing either by myself or my grandma, as though it had been just another thing that happened during that summer. Or maybe they had known, but they hadn’t said anything to me, as though to meet her in that way was just another standard step in my education, as though seeing a woman so close to death, so close that she no longer looked human, still doesn’t give me nightmares.

***

The second time I heard the sounds of someone dying, I was thirty-two, freshly married, lying next to my husband in bed. My husband’s snores had woken me up again, and I was staring up at the ceiling, seeing shapes in the shadows cast from the streetlamp outside.

The ways of the light and the shadows in this place were not yet familiar to me; we had moved into this downstairs apartment a few months earlier. Directly above me, past the shadows on the ceiling and the paint and the wood and the insulation and the carpet, was our landlord’s bedroom. In fact, I knew that Mr. W’s bed was in the same position as ours, between the windows. On nights like these, I could hear the creaks of his bed as he shifted about or the sounds of his footsteps moving to and from his bathroom, which was stacked directly above ours.

Our landlady, his wife, slept in a separate bedroom that was positioned above our living room. The concept of separate spousal bedrooms has long been intriguing to me, especially when I lie awake at night after having been woken up by my husband’s snores. Earplugs help, but they’re not foolproof. I learned this lesson growing up; my father is also terrific at snoring. At one point during my childhood, he began to sleep in the backyard in a tent when the weather was nice. This was a great set-up for my parents, but it was less so for me, whose bedroom window faced the backyard and seemed somehow to serve as a microphone for his symphony of wheezes and snorts. When my sister got older and moved out of the house, he took over her room—which again helped me none because our bedrooms were right next to each other. My parents credit sleeping in separate bedrooms with being a key factor in their long and successful marriage. Though what effect sleep deprivation has had on me is anyone’s guess.

For Mr. and Mrs. W, who have been married for at least half of a century, I can’t be sure that they had separate bedrooms for many years. But I suspect they had them now as a way to manage Mr. W’s deteriorating health due to Parkinson’s. In addition to having difficulty with physical movement and cognitive ability, people with Parkinson’s often have problems with sleeping, such as frequently waking up throughout the night and falling asleep throughout the day. This kind of sleep instability can increase feelings of anxiety, anger, depression, frustration, and loss of motivation. When my husband and I moved in, we met Mrs. W first, and she told us of Mr. W’s condition; she apologetically warned us about the outbursts he might have. Days later, standing in our shared laundry room and loading the dryer, I heard Mr. Wroar. The irritation in his voice was thick. When I returned to unload the dryer, Mrs. W came into the laundry room for cleaning supplies and told me that his physical therapy exercises had become more challenging, and he was having a harder time completing them.

Several times, we also heard loud crashes overhead; at least twice, my husband ran upstairs to help Mr. W off of the floor. One particularly brutal fall, one we hadn’t heard, required Mr. W to get plastic surgery on his cheek.

***

Here is a man, once brilliant, once strong, now trapped within his body. He knows what is happening to him; he knows it will only get worse. Once, he was a psychologist; he understands the mechanisms of his brain better than most people understand their own. He knows he can’t trust it as he once did. His brain now creates confusion. His brain now is a study of loss. He cannot rely on the messages it sends to the rest of his body or the way it interprets the messages it receives.

From his tufted armchair, legs covered by a neatly folded plaid blanket, he watches his wife, a petite woman with hair as short and white as his, move around their house. He watches her as she makes calls and confirms appointments as she handles the business of being a landlady. Through their large, light-inviting windows, he can see her rake up the leaves on the lawn. Or repaint the back porch, sweeping over large areas with big brushes and then switching to small brushes to work in fine detail and fix the trim. Her hands are nimble and precise. He can see her pull out a ladder from the garage and manage to balance on it as she clears out the rain gutters bordering the house’s roof. (He would be helpless if she fell.) Obstinately tenacious and tirelessly optimistic, she pays the monthly bills, fills up the gas tank, and wakes up early to do various volunteer work. In the backyard, she has placed a stone with the inscription: “Do not resent growing old. Many are denied the privilege.” She keeps her fingernails gracefully manicured, she matches her simple earrings to her top, and she drives her husband to different counties—even different states—for therapy, surgery, and visits with specialists. He sees her playing with their grandkids, who run through the house and jump and dance and hold colored pencils tightly to draw animals and write funny poems. And so he sits there, and he watches.

***

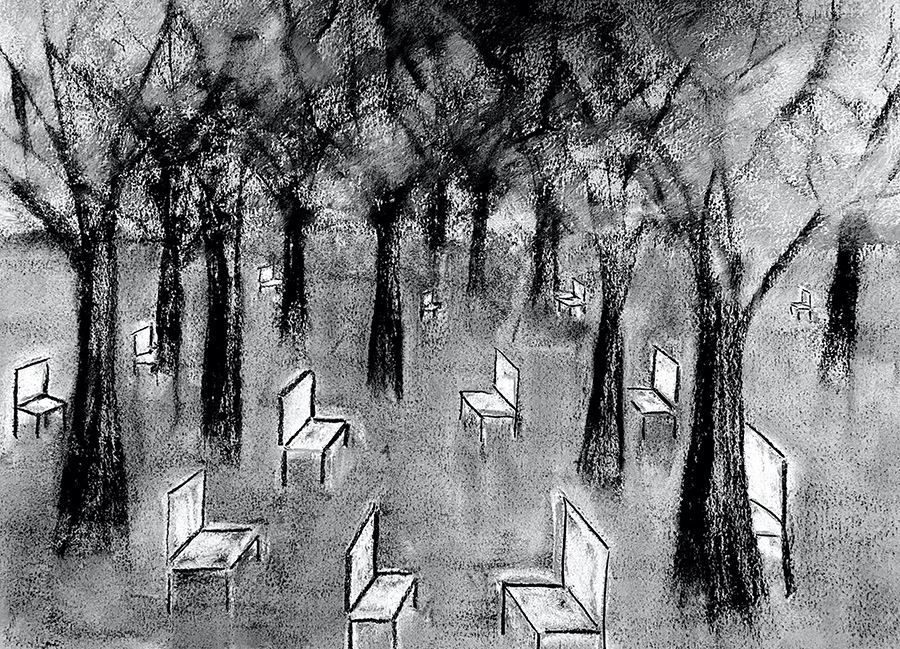

It is a wonder Mr. W doesn’t yell out in frustration more often, roar in revolt against the creeping disease that is overtaking the functions of his body, his life, his joy. If he were to stand on the hill that is his front yard, looking out onto the neighborhood sloping below him, and scream and scream, the whole city would forgive him. I wish I could tell him that I would stand beside him if he wanted me to. I could hold his hand. I know his wife would do the same, as would the rest of his family. The neighborhood could join us; the whole city could join us. We could all stand hand in hand. We could all scream with him, giving it the best our lungs and vocal cords could do—to recognize our own mortality but also, for a moment, to defy it.

Our screaming would be our own. Controlled by us. Allowed by us. But that one night, when I was lying awake next to my snoring husband, staring at the ceiling, the sound that rang out through the darkness came from that deeper place, that place beyond our jurisdiction. I recognized it right away, and my blood went icy: a ragged, high-pitched shriek that drowned into a mournful, muffled groan. A second sound followed, something like a sob. My stomach dropped. My heart exploded: thud thud thud thud thud thud. I was twelve again, in a bathtub of dark water, looking up at streetlamp shadows streaking across clothes hanging from a line, clothes twisted and contorted, paused in their purpose, waiting to be filled with human bodies. I was again frozen and terrified. I waited without breathing for the next cry, but it was quiet.

I sat up in bed and tried to breathe deeply, to slow my heart rate. I reached for my bedside bottle of water, opened it quietly, and took a few slow sips, trying to feel the liquid sink into me. My husband’s snores came back into my focus. They had become softer and more steady, as though respectful to the situation. He had turned on his side, his back to me.

The night became gentle again. I lay back down and curled against my husband, my forehead against his shoulder blades, feeling his chest expand and shrink and listening to the delicately musical breathing that accompanied it. I wondered if Mr. W had fallen asleep now or if he had been asleep this whole time. Would he know what sounds had escaped him? Were they present in his dreams? Something tells me he had been awake, had been lying in his bed and staring up at his own ceiling, seeing not the walls of his shelter but those of his confinement. I don’t know if Mrs. W had heard him; I heard no footsteps coming to his room, no voice to check if he was okay. Maybe she was too familiar with these sounds already. I felt and listened to my husband breathing for a long time before I was able to fall back asleep.

***

To think back to those visits with my grandma is to also think back to a house filled with snoring. A formidable foe to my father, she would offer deeply guttural snores at a lower range than what my father could do. If my father’s snores could be played on a cello, hers could be played on an upright bass.

My grandma hasn’t been doing well in recent years. Difficulty walking, back pain, memory loss, confusion, and other health issues have dramatically altered her ability to take care of herself or others. She cannot travel; she was not able to come to my wedding. It’s been a while since I heard her snore.

They tell me some lady’s going to start coming here, she says to me over the phone in a lucid moment, our voices carrying across continents. Some lady in my house, to cook in my kitchen, to bathe me in my own bathroom!

Grandma can’t bear the idea of moving into an assisted living residence; she sours equally to the option of having a nurse check in on her regularly. She worries loudly about the cost. I suspect she also worries about her dignity, but on this topic, at least to me, she stays quiet. My mother and my aunt alternate living with her as long as their schedules allow, sometimes spending months at a time each in that fifth-floor apartment in Sosnowiec, Poland. They do what they can to minimize the number of weeks where she is without one of them before the other one can come and take over.

During those weeks when her daughters are not there, my grandma is visited by women of the neighborhood. A sisterhood of caretakers. They bring groceries or homemade food; they sit and watch TV with her or talk about her restless-leg syndrome. They check if she’s taken her medication; they wash her dishes. Occasionally, Grandma allows someone to do her laundry. These days, she’s got a nicer washing machine, but clothes still hang to dry on the lines above the tub or, if the weather is nice, they can be strung up in the sunshine on the balcony. At least on the balcony, they can move in the breeze.

***

I stand in the shower that is positioned exactly below Mr. W’s shower. Under the steaming water, I draw handfuls of hair from my head, an indication that the hypothyroid medication I will take for the rest of my life needs an updated dosage. I paste my hair strands to the shower wall and sometimes nudge them around with a fingertip, drawing a mouse or a boat or the crown of a badger lord. I wonder sometimes how it will be. Will my hair fall out entirely someday, or will it be cut for the convenience of my caretaker? Will my husband hold my withering hand and murmur still how much he loves me? Will he die years before me, and will I have my own daughter or neighbor to make sure my refrigerator is not empty? Will I have to take care of my husband, make his appointments, always rake the leaves myself, apologetically explain to people some aspect of his condition? I wouldn’t be able to lift him by myself now, in my thirties—will there be someone around years from now to help me pull him up in case he falls? Will one of us hear the other’s sounds, the sounds we make when we are dying?

I’ve been thinking differently about snoring these days. I still get annoyed when my husband’s snores wake me up even though I’m wearing earplugs. I still want to laugh out loud during family visits when I can hear the concerto my dad performs. But in those dark and otherwise still moments when I’m staring at the ceiling, sitting on the bedside drinking water, or watching my husband sleep, I think: This is an audible confirmation of life. I can hear you living.

Contest Judge Sarah Gerard on “Can You Hear Me?”:

This author haunts us with sensation and sound, and forces us to feel the underlying theme of all narrative: time. The creeping approach of death. We hear it in the steady drip of water in the bathtub, the silence between sounds, feel it in the shedding or cutting of hair, the breath of love sleeping next to us, the movement of neighbors in apartments above and below, the stillness of an emaciated body lying before us. The proximity of lives slipping away, slowly or quickly, the fear of loss. The echoing words of her grandmother in Polish, saying: Old age is nothing joyful.

Monika Dziamka is a writer and editor from Albuquerque. She has an MFA in creative writing from Queens University of Charlotte, a Master’s in publishing from Columbia, and a BA in journalism from UNM. As an editor, she has helped hundreds of authors publish their novels, memoirs, mysteries, academic textbooks, and more. Her own creative writing has appeared in New Mexico Magazine, the Chicago Review of Books, River Teeth, and elsewhere. Monika is also a volunteer with the Read to Me! ABQ Network, which promotes childhood literacy and distributes gently used books to kids around Albuquerque and Bernalillo County. Connect with Monika through www.monikadziamka.com.

Mary Amato is a multidisciplinary artist currently teaching at The Montclair Art Museum. Her work has appeared in publications, including Quarter Press, Pulse, Peatsmoke Journal, 100 Word Story, New Note Poetry, SoFloPoJo, Viewless Wings, Sheepshead Review, HeartWood Literary Magazine, Unsung Hero, and more. She is also an award-winning novelist, poet, songwriter, and the co-founder of Firefly Shadow Theater, a company that explores storytelling with cut paper, light, and the human body. In her teaching, she specializes in working with adults who have cognitive disabilities or a fear of creative expression.

Squash Blossoms • Merridawn Duckler

By Anthony Yarbrough

By Noor Al-Samarrai

By Nancy Beauregard

By Harley Tonelli