BMR: Can you give us a little bit of background on yourself? In particular, what drew you to the vocation of the writer?

DD: I’m from New Mexico. I grew up reading and also spending a lot of time out in the New Mexico landscape, and I think that words and land oftentimes come together in a way that make us want to express ourselves, so I feel like the connection between the landscape and the weather and the sun and the clouds in New Mexico is much of what drove me to want to express the beauty I saw out there. Also, I did a lot of wandering. I went through high school—I spent a year in Sweden, I spent two years at an international school, and then took a year off to become a juggler, and then I went to college and got my English degree. And then I just sort of wandered around for a while; I managed some cafes, I worked as a bartender, I travelled to like 25 countries, and all that wandering really just—the whole time I was journaling and writing a lot and eventually I realized that this is how I make meaning of all these life experiences. So it came to me late in life; I don’t think I decided I wanted to be a writer until I was 28 or 30. But by that time it really hit me hard, and I think it’s because I had so many loose life experiences that I wanted to use writing as a way to make sense of everything.

BMR: Can you talk a little bit about your process, especially with regard to Archaeopteryx?

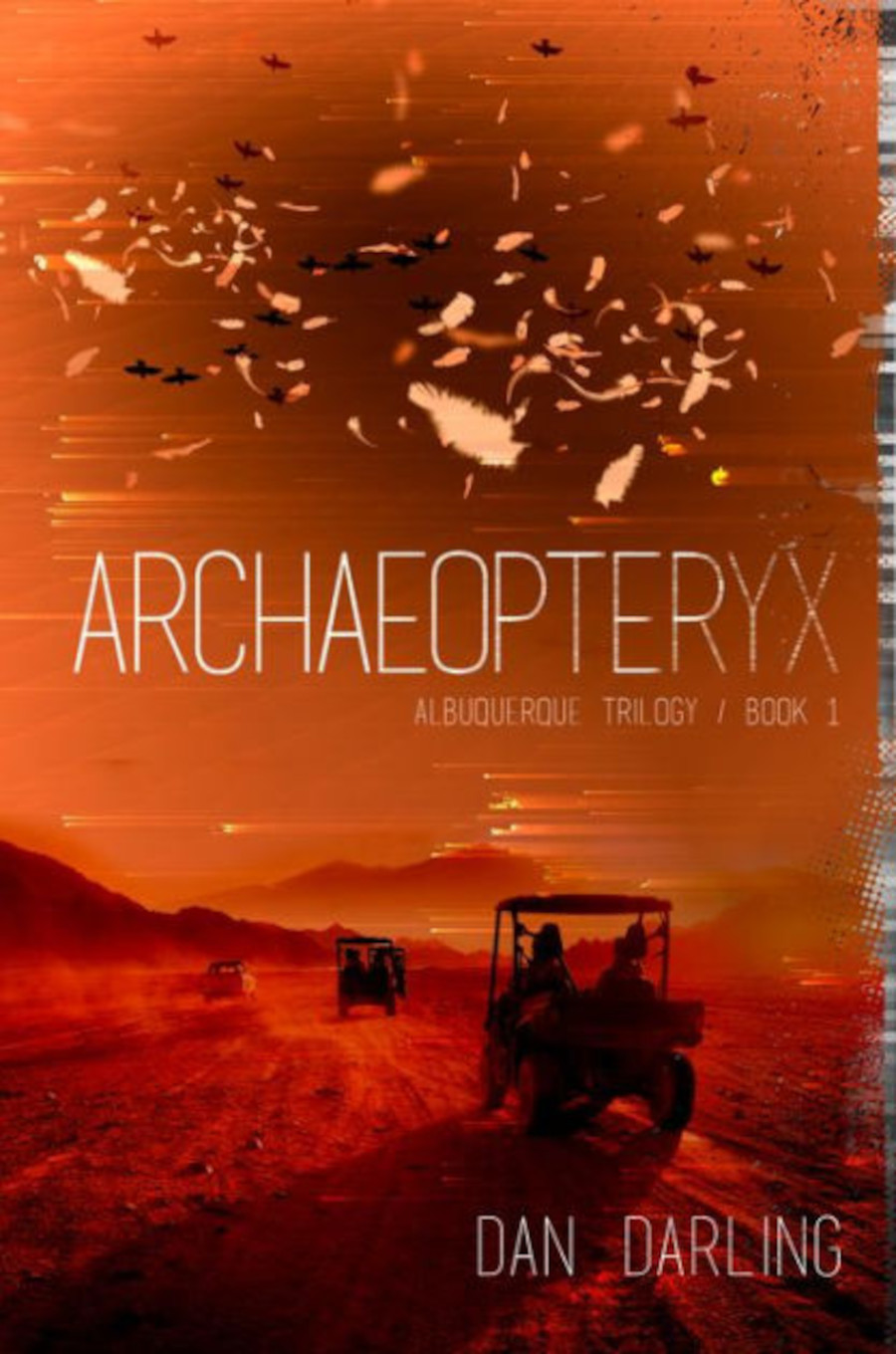

DD: Yeah, well, that’s a great question. One time I was helping a friend work on something for her dissertation, and I wrote up a little piece of paper for her, a little few hundred words, and she was like, “Dan, you’re a real drafter, aren’t you?” implying that my first draft was terrible (laughs). I wrote my dissertation for my MFA at the University of New Mexico, it was a novel…a western heist narrative, and at the end of it I thought it was sort of stupid (laughs). But I really liked the characters that I’d come up with. So that story sort of forged the characters that I thought had depth and richness, and I thought, “Ok, now that I know these people, I know what story I actually want to tell.” You know, I rewrote every word of the dissertation to come to the first novel, Archaeopteryx, and I think it was because it took me that long to get to know the characters and once I did I realized I wanted to tell a very different story. So, in terms of my process, it’s very revision heavy.

BMR: I wanted to talk a little bit about representation, representation being a topical and important issue, not only in literature but across fictive media. Considering that the protagonist of your novel comes from a different ethnic and cultural background than you do, what are your thoughts on the issue of representation? Are there ethical concerns that fiction writers should grapple with if they choose to write from the POV of characters of other ethnicities or cultural backgrounds?

DD: Yes (laughs). Yes, yes, yes. I think that, you know, you could talk to smarter people than me about this issue, but at the time, when I started writing about John Stick, who is half-Chicano, half-Caucasian—I’m a person who really believes in equity across racial and cultural boundaries, and so I’ve always been drawn to the plight of non-Caucasian people in our country, especially in a colonized and recolonized land like New Mexico. So, when I came up with Stick’s identity, I was sort of, like, wanting to chase after this hybridity that is bred in the borderlands, and…even though I myself am Caucasian, I oftentimes feel, as a person, you know, sort of drawn to different polarities. So, I sort of wrote him—I’m not sure if I should have? I don’t think I will ever try to write a person of another ethnicity again, just because there’s a lot more resistance to that now, I think, rightly so. It’s a form of appropriation, no matter how good your intentions are or how well-informed you are, and we can have arguments about Tony Hillerman all day long if we want to (laughs). But these days, I think we need to err on the side of caution, so I wouldn’t go that route again, even though I really want to imagine myself in the world of another person, especially another person very different from me. I just don’t think in today’s literary landscape that’s a responsible move.

BMR: Going back to the idea of Albuquerque and its influence on you as a writer: you grew up here and have said that you’re “obsessed with the desert” and its “sacred, dry places.” In your mind, what role does setting play in fiction, kind of generally speaking, and more specifically, what role does it play in the literature of New Mexico?

DD: I think setting informs everything about a work of fiction, because people are born in a place and that place transforms them or grows them into who they are, and so John Stick would not be the person he is unless he lives in Albuquerque, and I wouldn’t be the person I am unless I was born in Albuquerque, so in a way, the realization of the setting is like the soil for everything else to grow out of: the conflicts, the characters, the themes, the language. I think it’s where you start, whether you really realize it or not, but I think some of the greatest fiction is really grown from the earth, from the setting itself.

BMR: Could you maybe give some advice to aspiring writers, especially in terms of getting their work out there—“marketing” and “branding”—terms I hesitate to use, but which are probably germane to that discussion? Should you find an agent, or self-publish? What are your thoughts on that?

DD: You know, it’s becoming much more and more incumbent on a writer to have a brand, to be a self-promoter and to be a networker, and to have all those skills. I think in many ways, those skills are as valuable as your writing chops. So, I think that developing those, and implementing those, is key. I…published my first book a few years ago, and since then, my publisher went under pretty quick…it wasn’t ’cause of me! (laughs) They were on their way out. I didn’t know that when I signed up with them. When I signed up with them, I thought they were awesome; all the authors there were happy, and then as soon as I signed the contract, things started going downhill. Any-ways…I’ve been looking for a new publisher since then, and if you’re going to go for one of these, you know, big house publishers, they expect you to do a lot, and to really have your own sort of machine of social media, and branding and marketing and networking, and it really helps to do that. It helps to make contacts in New York and other places where you can start getting to know agents and stuff…having those skills is awesomely helpful. I would say, as far as self-publishing versus getting traditionally published, and this might be in flux, but [in terms of] self-publishing…you’re going to spend a lot of money, and very few people are going to actually read the book. And so I think that, unless you have a super large following of people who are going to read your book, because they know you—like if you’re a YouTube star or something—then you want to get that link with a publishing house, because they can get it out there. You know, when my book came out, it was through an indy press called Curiosity Quills, which is now defunct, essentially, but at the time, they had a good marketing team, but it sort of disintegrated, and so we were left to do a lot of the marketing on our own, which involved trying to get books into bookstores, etc. And we worked really hard on that and got my book into a handful of bookstores, and it took a ton of work, and it wasn’t, in the end, commercially worth it, financially worth it. You know, it’s a tough world out there for writers. There’s tons of competition now—everybody has a book—so I think going the traditional route is preferable because you get more help, and they have these fingers out into all these bookstores and different avenues to sell your stuff.

BMR: Similarly, what advice could you give on processing or coping with rejection letters and negative reviews and all that sort of stuff that you have to contend with?

DD: This goes back to—[your] question about agents—probably, if you’re a fiction writer, you write a novel and you want to get it out there, you’ll need an agent, a literary agent, because most presses don’t take unsolicited manuscripts. So you want to get a literary agent. Part of soliciting an agent is sending out tons and tons and tons of queries—these letters where you’re like “Please be my agent, here’s why my story is great, here’s why I’m special.” It’s so time consuming, and so morally degrading, but—yeah, you’re going to have to get used to rejection. I feel like, as a writer, you shouldn’t even think of it as rejection, you know? You’re sending a bunch of short stories out there to literary magazines, for example. That’s what we should all be doing in graduate school and beyond, if we write short stories, is just try to get them out there to literary magazines, because you’re going to get picked up and published, there’s no doubt about it. But when you get a “rejection,” you shouldn’t even see it as a rejection. You should think of it as, like, they preferred something else for the moment. It’s not like they’re telling you “You’re no good”; they’re saying, “Oh, we picked something else for now.” And we just have to get used to that…That’s nothing about your story, that’s about [them]. And that’s how we have to view it when we’re sending queries out to agents or short stories to literary magazines. It’s not about our story or our novel, or ourselves, it’s about them, and they might just not prefer what we’re doing.

BMR: What to you are the most crucial elements of good writing?

DD: As a reader, I want interesting language, and interesting, grabbing visuals and images, right away in story, and I also want immediate— a sense of dramatic conflict that’s going to pry open this chasm that forces itself through us the way of the story or novel. So that’s what I look for. I’m one of those people who, when I walk through a book store, and I pick a book off the shelf and I read the first sentence, and if the first sentence sucks, I won’t read the book. (laughs) If it’s awesome, then I’m likely to read the book. I think, though, I think about my students and what they’re interested in, and a lot of my colleagues are very critical of this word, but it’s a word that I hear from my students over and over: that the book is relatable, or that the story is relatable. They want to feel like they can see themselves in this character’s thoughts and plight and problems and joys, and so I think if we’re talking about appealing to young readers, then we want to think about the idea of relatability.

Darling’s debut novel, Archaeopteryx, was published by Curiosity Quills press in 2017. Blending magical realism with noir, it tells the tale of John Stick, a zookeeper at the Albuquerque Biopark, who finds himself at the center of a plot involving chupacabras, a racist militia, and his own identity as an outcast.

To learn more about Dan and his work, visit him at dandarling.net.