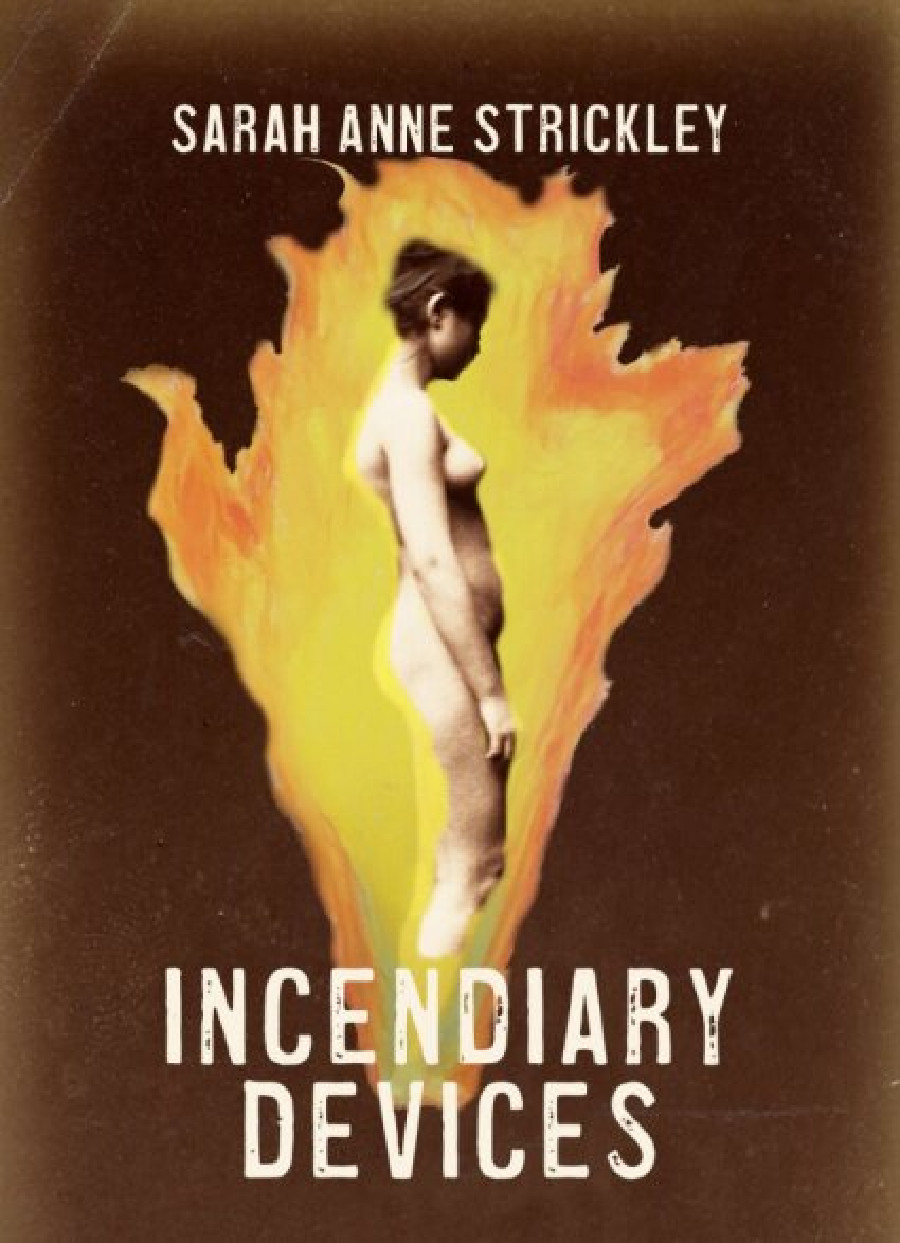

The first two immediacies that must be considered when sending a book out to stake its place in the world are, of course, the cover and the title. When I first saw the cover of Incendiary Devices with its naked, burning feminine figure stamped firmly in the center of a charred blankness, I knew Sarah Anne Strickley was out do so some serious blazing. The very first short story, “A Story From the Perspective of the Flame,” expands the cover by giving us a woman self-immolating in her kitchen with cooking oil and a match as one of over a hundred who have committed the same self-destructive act as a response to the oppression of male violence. This chilling image sets the precedent for the rest of the book with a quick, clear spark. Sharp and on edge, Strickley fires us into her new collection of stories by asking: “What is at the root of such a horrifying phenomenon?” There is no space here for dawdling humility or a casual touch. There is nary a sardonic note. Each story is pointed back to this question with burning precision. The question is, itself, incendiary. This book is, indeed, an array of incendiary devices.

Strickley constructs her stories with remarkable narrative skill combined with the astute edge that comes with the inherent and specific violence of being a woman in America. Having spent most of my life in the American Midwest and South, the way the men in her stories speak, think, and act could be the men I grew up with. They are complex, genuine, and shaped by their own complex, sometimes violent, personal histories.

Some of them inspire empathy and understanding. In “Chronology of a Disaster,” Trace has a difficult time with marriage but loves his twin daughters. Many others inspire rage and confusion but maintain an unnerving everyman familiarity. Some are trying to do the right thing. Some of them are “nice guys,” like the narrator’s grandfather in “How to Write Your Rape Story,” who meets his wife in his dangerous junkyard stomping grounds after she escapes her abusive boyfriend in the dead of night. He saves her from possible peril by approaching her with a flashlight, but not without letting the unsurety of his intentions linger in the air for a moment. Some embody the flagrant transgressions—the wild cards women are always having to look out for who prevent us from ever moving comfortably in our world. For example, in “Dismember Me, Baby,” Bill purchases murder supplies after moving in with Caroline because he doesn’t like the way she’s unpacked and organized his possessions. Caroline can’t tell if he’s joking or not when he says, calmly, about the window seat she has placed his clothes in, “Maybe we should cut you into pieces and stuff you in there.” As he leaves to maybe or maybe not get the murder supplies listed in their uncomfortable extended riff on the “joke,” Caroline leaves the apartment, too, but she doesn’t come back. She makes her plan, acts carefully, moves to Colorado, eventually starts a family—but she lives with the fear that he might find her again one day. Her moves are questioned and attacked for the rest of her life by people who know Bill as “a great guy.” “Dismember Me, Baby” is particularly haunting because of the quotidian circumstance in which the sudden and shocking inciting incident is enveloped—Caroline isn’t even sure if she heard him right. The characters aren’t heightened in any dramatic literary fashion—a defining characteristic of most of the stories. They are terrifyingly real. How can we know who the Bills are until they suddenly say the one line that changes everything into a hellscape?

These stories also contain love and the possibility of love. We want Trace, a mild but confused twice-divorced dad in “Chronology of a Disaster” to be able to find love again. Ollie loves Sky in “The Angel of Stewart Beach,” one of the more tender stories in the collection. They’re flat-broke, about to be evicted from their small apartment, considering that they might be at an end. Ollie loves Sky enough to consider asking her to marry him to save their partnership, but not quite enough to not leave her alone at a crucial moment. When he sees her again later in life, he wants to embrace her, but his transgression, though not an intentionally malicious one, was still bad, and she rejects his embrace with a short shake of her head in a heartbreaking moment that makes us want to rewind time for Ollie. But, as Strickley writes in “Local Missing Girl:”

“…time keeps happening. You can try to make life hold in a decent spot, but it never will. The other problem is that life always heads in the direction you’ve knocked it. Like the trash they dump in space. It’ll keep on going that way forever unless it collides with something else.”

Ollie can’t go back to fix his mistakes. Neither can Trace. No one can. Decisions have consequences, even if they’re not the decisions you would have made if you went back in time immediately after transgressing.

One of the core tenets of storytelling is that a character must make a decision. This is what dictates motion, change. In most situations, there are the actors, and there are those who are acted upon. Responsibility is a fact that we need be reckoned with by someone, somehow. Where does responsibility lie? This question is interrogated in “Rear Window Redux,” in which Will, a victim of childhood abuse, considers what it means to be complicit. He believes he’s never done anything wrong. He’s seen a lot of bad stuff without intervening, but he’s comfortable because he has always held back his own rage from turning into actions he can’t take back. He believes he is morally safe. Where does he lie on the spectrum of responsibility?

The impossibility of knowing what actions lie in someone’s future lies at the heart of this book and fuels the tension that is the book’s engine. What will Mr. Meyer do to his wife next? What will Terry, a chaotic mischief-maker with haughty opinions about love, do to Katie once he gets her in his car? We want to believe these characters will not harm people.

We want to be able to love people and get close to them. We want wrongs to be made right. But, Strickley is telling us, these wants are often mucked up by the unfathomable qualities of the other that we can never understand. The narrator in “How to Write Your Rape Story” will never know why her grandfather let his future wife wait in the flashlight in the junkyard. The narrator thinks it through and lands on a reason. But it is constructed without her grandfather’s verification. Most of Strickley’s characters have an assortment of unknowns they will never have answered. This realm of the unknown is what Strickley is great at highlighting with these stories. And the unknown mixed with the truth of violence is a source of immense sadness.

Sarah Anne Strickley is the author the novella, Sister (Summer Camp Publishing, 2021) and the short story collection, Fall Together (Gold Wake Press, 2018). She’s a recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Creative Writing fellowship, an Ohio Arts grant, a Glenn Schaeffer Award from the International Institute of Modern Letters, the Copper Nickel Editors’ Prize for Prose and other honors. Her stories and essays have appeared in Oxford American, A Public Space, Witness, Harvard Review, Gulf Coast, The Southeast Review, The Normal School, Ninth Letter, Hotel Amerika, Copper Nickel, storySouth, and elsewhere. She’s a term Assistant Professor of creative writing at the University of Louisville and serves as faculty editor of Miracle Monocle, UofL’s award-winning literary journal.

Incendiary Devices is available for sale from Small Press Distribution at https://www.spdbooks.org/Products/9781948800570/incendiary-devices.aspx