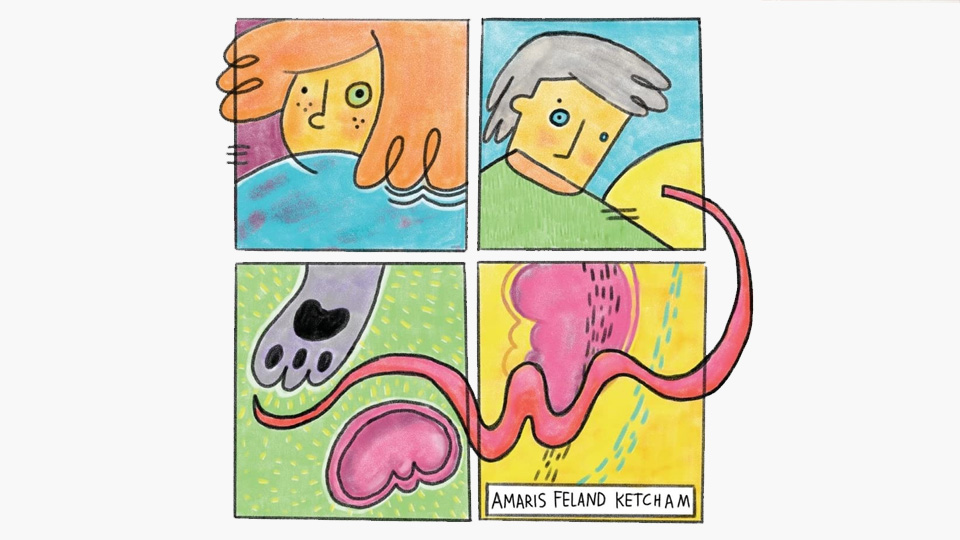

Amaris Feland Ketcham occupies her time with open space, white space, CMYK, flash nonfiction, long trails, f-stops, line breaks, and several Adobe programs running simultaneously.

She is the author of two poetry books, Glitches in the FBI and A Poetic Inventory of the Sandia Mountains, and the Best Tent Camping: New Mexico guidebook. Her award-winning writing has appeared in Creative Nonfiction, The Los Angeles Review, Prairie Schooner, Rattle, the Utne Reader, and dozens of other venues. She teaches in the Honors College at the University of New Mexico where she is the faculty advisor for the nationally acclaimed arts and literature magazine Scribendi. She has painted murals throughout Albuquerque, acted in a radio drama about the Badlands National Park, and taken students on multi-week camping trips along the Lewis and Clark Trail. Amaris also stages creative encounters with patients as a poet and artist with the Arts-in-Medicine program at UNM Hospital.

What were your intentions initially in starting a graphic diary? Did you imagine that you would end up sharing it in this way?

I always respected people who kept regular diaries. I had never kept up a daily writing practice that didn’t involve a particular project—usually I am exploring some idea or question and it becomes an essay or series of poems or something in between. But, I started keeping a diary shortly before the pandemic began, and soon, wanting to improve my drawing skills, it morphed into a diary comic. When I took on the challenge of making a daily comic, I’d expected to draw about hiking, birdsong, and the mere mundane details of my life—a practice that would produce nothing interesting to share. It wasn’t until I was in a show at 1415 Gallery, where I shared a zine compilation of the comics from January 2022, that I realized other people might be interested in reading them. At that show, several people came up to me and thanked me for my vulnerability. We had just learned that the CT scan showed a nodule, and my husband would need another surgery. That collection ended on the forsythia comic. So, at the show, several people wanted to talk about their medical experiences, their cancer experiences. I think that’s one of the powerful connections that memoir provides us.

Who are some other comic artists or memoirists who you feel most influenced your art?

Definitely Lynda Barry! I think that Barry has inspired so many people to re-engage with their creativity and to start keeping diaries. I love John Porcellino’s King Cat comics, both his style and his fluency in moving between memory and poetic vignettes. As far as the actual drawing goes, I try to think more about Tintin and newspaper strips and how to draw panels that have a cartoony, goofy simplicity. I am less interested in rendering something so it looks “realistic” and more interested in being a little playful and embracing errors. I think that adds to the drawings looking like they were made by a person. (It also helps to embrace errors when you have a daily practice, because you must finish the entry with your coffee—from concept to story to drawing, you must be quick!)

What was the process of developing yourself and your loved ones into comic avatars like?

You can probably tell the characters change and are a little more refined throughout as I settled into what our drawn avatars looked like. It takes a while to figure out the telling details, what to emphasize on each character. For my own avatar, I settled on freckles, big hair, and trying to be consistent with the nose, face shape, etc. A couple people have told me that she doesn’t look anything like me. My own mother said, “That hair keeps getting bigger and bigger! You know your hair isn’t that big!” But the point isn’t that this character actually resembles me in a literal sense. Rather, she is my stand-in. And cartoons should exaggerate a little.

At the bottom of each entry you include a meal from the day and also a story you encountered in the news. I liked how this painted a very holistic image of the day. Not only do you put important events into panels, but you also show us something small within your control (a meal) and something large outside of your control (global news events). Where did you get the idea to do this? Were there any connections or patterns this practice allowed you to see?

I wanted a way to mark the days. It is also part of my “warm-up” for drawing the comic, just remembering something I ate the day before and scrolling a little through the news, then working on the title. For about a month after the first surgery, my husband could only eat soup—so that ended up being documented, including hints of my frustration with the lack of variation, (One entry notes the pea soup was uninteresting; by the time we got to sausage and cabbage in milk broth, I was very tired of soups.)

A couple people have pointed out that many of the headlines are related to COVID and that in a way, it’s a COVID diary. I wouldn’t necessarily call it a “COVID diary,” but it is pretty firmly set during the pandemic. Our social circle contracted quite a bit during that time, so there aren’t a ton of other people in the book—even my work was often empty and I would be the only person in the building. But I think just as many headlines are about climate change or strange things that caught my eye (such as the meteorite crashing through a woman’s roof).

As your husband’s time in the hospital came to an end, I noticed an increased focus on nature, specifically birds. Was this an intentional shift?

Yes, it was intentional—or, at least the shift to nature. To convey the anxiety of the surgeries and hospitalizations, many of my comics became a little more abstract. I hoped that the nature comics would show a kind of re-grounding and renewal, as well as an attention to the world outside of one’s own head. Quite a few at the end are spring haiku. I hadn’t realized I included so many comics about birds!

What is your favorite bird?

That’s a tough choice! I think in the yard I am most partial to the thrasher and his crazy song, the black-chinned hummingbird who is always ready for a fight, the woodpecker and his persistent knocking, and the roadrunners and their games of chase.

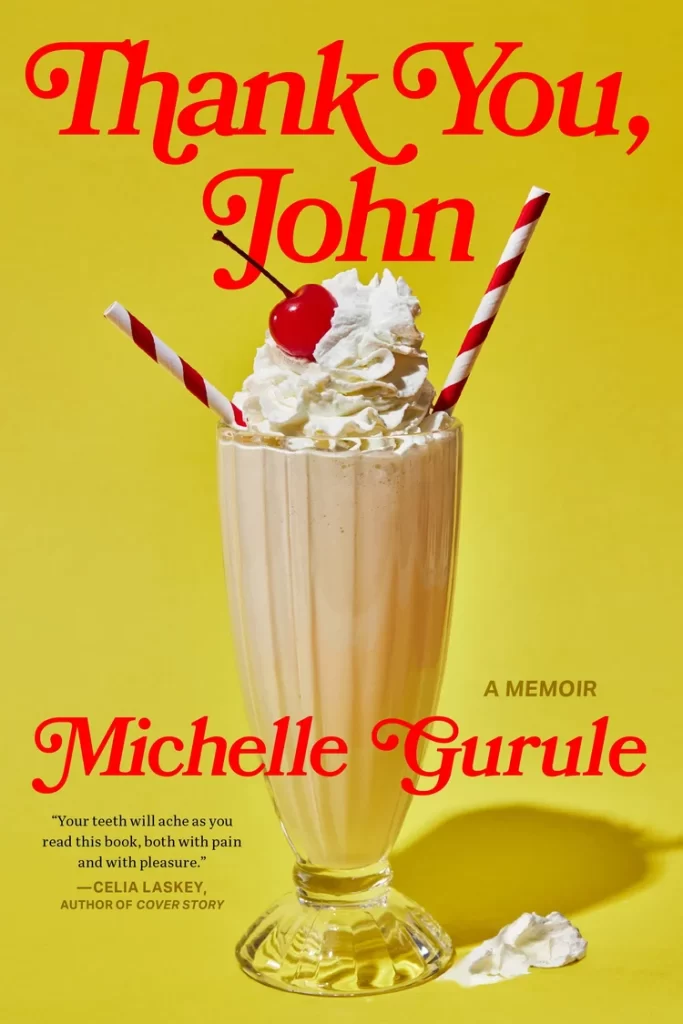

What do you hope this memoir will give to your readers?

Hope. Cancer is such a daunting medical experience, and it always comes out of the blue. And it’s something that affects everyone eventually, either because you know someone with cancer or in remission, or a personal diagnosis. It’s often very difficult to find the ways to talk about and process medical diagnoses and treatments, but I think that’s one of the ways that graphic medicine excels, because it can connect with people on an emotional, cognitive, empathetic, cultural, and aesthetic level.

Would you encourage others to practice keeping a graphic diary? What advice would you offer for starting one?

Absolutely! Making a diary comic is a lot of fun—and one of the nice things about diary comics is that you can focus on the mundane aspects of your life. I have read diary comics about taking out the trash, folding fitted sheets, and scooping up dog poop from the yard. As far as what incites the story, the stakes can be pretty low.

When I started my diary comic, I was often dismayed at how “bad” my drawings were. I couldn’t even draw my cats consistently. It’s really easy to give up at that stage, but I would urge you to keep on working with it. Don’t feel like you must draw like anyone else. The way you draw is like the way you write—it’s individual and personal, wobbly weird lines and all.